The σ24 Subunit of Escherichia coli RNA Polymerase Can Induce Transcriptional Pausing in vitro

A. B. Shikalov1, D. M. Esyunina1, D. V. Pupov1, A. V. Kulbachinskiy1, and I. V. Petushkov1,a*

1Institute of Molecular Genetics, Russian Academy of Sciences, 123182 Moscow, Russia* To whom correspondence should be addressed.

Received November 2, 2018; Revised December 5, 2018; Accepted December 12, 2018

The bacterium Escherichia coli has seven σ subunits that bind core RNA polymerase and are necessary for promoter recognition. It was previously shown that the σ70 and σ38 subunits can also interact with the transcription elongation complex (TEC) and stimulate pausing by recognizing DNA sequences similar to the –10 element of promoters. In this study, we analyzed the ability of the σ32, σ28, and σ24 subunits to induce pauses in reconstituted TECs containing corresponding –10 consensus elements. It was found that the σ24 subunit can induce a transcriptional pause depending on the presence of the –10 element. Pause formation is suppressed by the Gre factors, suggesting that the paused complex adopts a backtracked conformation. Some natural promoters contain potential signals of σ24-dependent pauses in the initially transcribed regions, suggesting that such pauses may have regulatory functions in transcription.

KEY WORDS: transcriptional pausing, RNA polymerase, alternative σ factors, Gre proteinsDOI: 10.1134/S0006297919040102

Abbreviations: nt, nucleotides; RNAP, RNA polymerase; TEC, transcription elongation complex.

The σ factors play a crucial role in the process of transcription

by allowing RNA polymerase (RNAP) to recognize different classes of

promoters. All studied bacteria have the principal σ subunit

(σ70 in E. coli) that is needed for

transcription of housekeeping genes [1, 2]. Alternative σ subunits can recognize

promoters that are significantly different from those recognized by the

principal σ subunit and control gene expression in response to

changes in the environment and stress factors. In E. coli, six

alternative σ subunits were found, which could be divided into

two families according to their protein sequence, σ70

and σ54 [2, 3]. The first family includes σ70,

σ38, σ32, σ28,

σ24, and σ19, while the second has

only σ54, which differs significantly from the others

by the structure and mechanism of action; unlike σ70

family members, it needs an activator protein and ATP hydrolysis for

transcription initiation [4]. The

σ70 family contains four groups of σ factors [2, 5]. The principal

σ70 subunit of E. coli is a member of group 1

and consists of four conserved regions (σ1, σ2, σ3,

σ4) as well as a nonconserved region (NCR) between σ1 and

σ2. Members of group 2 emerged from independent events of gene

duplications in different bacteria [6]. A

well-known member of group 2 in E. coli is σ38,

which lacks region σ1 and NCR. Analysis of the promoter complex

structures and amino acid sequences revealed a high level of similarity

between σ70 and σ38, which allows

them to recognize similar promoters [2, 7, 8]. The σ38

subunit is needed for transcription during stationary phase, plays a

role in stress response (osmotic shock, high temperatures), and also

participates in transcription at low temperatures [9, 10]. Group 3 is heterogeneous

and includes multiple subgroups [6]. In E.

coli the members of this group are σ32 and

σ28; their domain organization is similar to that of

σ38, but their sequences differ significantly and,

accordingly, they recognize promoters with distinct sequences [11, 12]. The

σ32 subunit recognizes promoters of genes during heat

shock response [13, 14].

σ28 recognizes promoters of genes responsible for

flagella synthesis [15-17].

The expression of this σ factor is also important for biofilm

formation [18].

Members of group 4 have only regions σ2 and σ4, which are necessary for the recognition of the –10 and –35 promoter elements, respectively [1, 2, 6]. Escherichia coli has two representatives from this group, σ24 and σ19. σ24 initiates transcription of heat shock genes as well as genes of the periplasmic stress response (triggered by increased levels of misfolded proteins) [19-21]. This subunit is also necessary for cell resistance to Cu, Zn, and Cd ions [22]. The smallest σ19 participates in the transport of Fe ions at low intracellular Fe concentrations [23].

According to the classical model of transcription initiation, the σ subunit leaves the transcription complex during promoter escape. However, it was later found that the σ70 subunit could stay bound to RNAP during the elongation phase of transcription [24-29]. Moreover, σ70 is able to rebind free transcription elongation complex (TEC) [30-34]. When bound to the TEC, the σ subunit can recognize promoter-like sequences, which leads to transcriptional pausing [35, 36]. The key signal required for pause formation is a –10-like element in the transcribed DNA, which is recognized region σ2 of σ in the nontemplate DNA strand [30, 36-39]. The –35-like elements as well as DNA sequences around the RNA 3′-end, which can promote TEC backtracking, can also contribute to RNAP stalling [40-42]. Although σ70-dependent pausing could be observed in both phage and bacterial genes [30, 36, 38, 43], the functional role of such pauses in most cases remains unknown (reviewed in [35, 44]).

Recently, we have shown that not only σ70 but also σ38 can induce transcriptional pauses, whose formation is dependent on the presence of –10-like elements [34]. However, it is not known if any of the other σ subunits in E. coli could induce transcriptional pausing. The goal of this work was to determine whether alternative σ32, σ28, or σ24 subunit could induce transcriptional pauses in vitro.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents. The following reagents and compounds were used: Tris, acrylamide, N,N′-methylene bis-acrylamide, urea, imidazole, magnesium chloride, sodium chloride, potassium chloride, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and rifampicin (all from Sigma, USA; purity >99%); EDTA from Dia-M, Russia; 99.2%), isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA; >99%), potassium dihydrogen phosphate and potassium hydrogen phosphate (Roth, Germany; >99%); lysozyme (Amresco, USA; ultrapure); nucleotide triphosphates (NTPs) (Illustra, GE Healthcare, UK; >98%), kanamycin and ampicillin (Sintez, Russia).

Protein purification. Escherichia coli RNA polymerase (RNAP) core enzyme with a 6× His-tag on the β′-subunit N-terminus was purified from the E. coli BL21(DE3) strain carrying the expression plasmid pVS10 containing all core RNAP genes under the control of T7 RNAP promoters. Protein expression and purification were performed as described previously [45].

The rpoH and rpoF genes, encoding the σ32 and σ28 subunits, respectively, were cloned into the pET29 vector between the NdeI and XhoI sites. The resulting plasmids pET29_rpoH and pET29_rpoF were used for transformation of E. coli strain 3013 (New England Biolabs, USA). An overnight culture of transformed cells (500 μl) was transferred to 500 ml of LB medium with kanamycin (50 μg/ml) and chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml, for E. coli 3013 pLys plasmid maintenance). IPTG was added to 1 mM at A600 = 0.6. In the case of σ32 expression, rifampicin (150 μg/ml) was added 30 min after IPTG to prevent transcription of chaperone genes to enhance formation of inclusion bodies. The induction was carried out for 2 h at 22°C, and the cells were collected by centrifugation. Inclusion bodies were isolated from the cells as described previously [46]. After renaturation, the protein mixture was purified by anion exchange chromatography using a 1-ml MonoQ column (GE Healthcare, USA), which was pre-equilibrated with buffer containing 40 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.9, 5% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA disodium salt, and 0.1 mM dithiothreitol. The sample was loaded at the rate of 0.5 ml/min and elution was carried out for 90 min using a linear NaCl gradient from 120 to 600 mM in the same buffer solution at 1 ml/min [47]. The σ32 and σ28 subunits were eluted at 17-22 and 38-43 min, respectively. These fractions were collected and concentrated with an Amicon Ultra-4 Ultracel-10K (Merck Millipore, USA) ultrafiltration system.

The rpoE gene encoding the σ24 subunit was cloned into the vector pLATE52 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using the manufacturer’s protocol. The resulting vector was used for transformation of the E. coli strain BL21(DE3). Cells were allowed to grow in 500 ml of LB medium with 20 ml aminopeptide and ampicillin (200 μg/ml). The induction was carried out by the addition of IPTG to 1 mM. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation and suspended in lysis buffer containing 50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM PMSF, 0.2 mg/ml lysozyme, and 80 U DNase I (Thermo Fisher Scientific). σ24 was extracted from cellular lysate by Co2+-affinity chromatography using a 1-ml HiTrap TALON crude column (GE Healthcare). The column was pre-equilibrated with buffer containing 50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, 500 mM NaCl, and 1 mM MgCl2. The sample was loaded at the rate of 0.5 ml/min, and the column was rinsed with 5 ml of the buffer. σ24 was eluted by the same buffer containing 200 mM imidazole. GreA and GreB factors were purified from the soluble protein fraction as described previously [48]. The purity of all protein preparations was ≥98% and the protein yield was from one to several milligrams.

In vitro transcription. To investigate the ability of alternative σ subunits to induce transcriptional pausing, TECs were assembled from oligonucleotides and core RNAP. Oligodeoxyribonucleotides and oligoribonucleotides were synthesized by DNA-Synthesis (Russia) or Evrogen (Russia) (see all sequences in Figs. 1 and 2). Radioactive label was introduced at the 5′-end of RNA oligonucleotides with T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs) and [γ-32P]ATP. The labeled RNA (250 nM final concentration) was mixed with the template DNA strand (2.5 μM) in TK buffer containing 40 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.9, 40 mM KCl. The sample was incubated at 65°C for 3 min and then cooled to 20°C at 1°C/min. After this, the sample was diluted 3-fold with the TK buffer, and then core RNAP was added to 190 nM concentration. The mixture was incubated for 15 min at 37°C followed by the addition of nontemplate DNA strand to 1 μM and incubation for an additional 15 min at 37°C. The resulting preparation was then split into two parts. To the first part, a σ subunit was added to 2.5 μM final concentration, followed by incubation for 10 min at 37°C. To the second part, the same volume of the protein storage buffer was added (40 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.9, 100 mM NaCl, 50% glycerol). Next, the assembled TECs were diluted 10-fold by the TK buffer pre-heated at 37°C, and aliquots for control samples were taken. In the case of reactions with GreA or GreB factors, they were added to the reaction mix at 1 μM concentration. Transcription was initiated by the addition of NTPs (100 μM each, final concentration) and MgCl2 (10 mM) and stopped after various time intervals by the addition of an equal volume of stop-buffer (7 M urea, 30 mM EDTA, 2× TBE). The transcription products were separated by 15% denaturing PAGE (19 : 1) and visualized by a Typhoon 9500 scanner (GE Healthcare). The pausing efficiency was calculated as the ratio of paused products to the sum of paused and longer RNA products. All experiments were performed in least in two replicates (3-5 times for quantitative analysis).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To investigate the ability of the alternative σ32, σ28, and σ24 subunits to induce transcriptional pausing, we (i) obtained purified σ subunits, (ii) performed in vitro assembly of TECs containing potential pause signals for these σ subunits, and (iii) tested the influence of the σ factors on RNA synthesis in such complexes. For our experiments, we assembled TECs from synthetic oligonucleotides carrying consensus –10 promoter sequences for each of the alternative σ subunits. An analogous approach was previously successfully used for investigation of E. coli σ70- and σ38-mediated transcriptional pauses [33, 34].

At the beginning, we cloned the genes of all investigated σ subunits, expressed them in E. coli cells, and purified the proteins. Control experiments showed that all three σ subunits have transcriptional activity and are able to direct promoter-specific transcription initiation by the RNAP holoenzyme (data not shown).

Formation of transcriptional pauses was studied using an in vitro system with reconstituted TECs assembled from synthetic oligonucleotides and core RNAP. Each TEC contained the –10 element consensus sequence for one of the studied σ factors (Cons-σ28, Cons-σ32, Cons-σ24; Figs. 1a and 2a) [11, 12, 49]. Previous studies of σ70- and σ38-dependent pauses showed that the distance between the 3′-end of nascent RNA and the –10-like element during its recognition by the σ subunit is similar to that between the –10 element and transcription start site (TSS) in the promoter complex [33, 34]. However, the pause is observed several nucleotides downstream since RNAP can add several nucleotides to RNA after pause recognition. Therefore, in reconstituted TECs the positions of the RNA 3′-end relative to the –10-like motifs corresponded to the distances between the –10 elements and TSS in natural promoters for corresponding σ subunits (Figs. 1a and 2a; the typical TSS position relative to the –10 promoter element is shown in yellow). Furthermore, known pause signals for the σ70 subunit can contain sequences favorable for RNAP backtracking at the pause site, which serve as an important component of the pause signal [41]. Accordingly, the reconstituted TECs contained such a sequence (shown in cyan at Figs. 1a and 2a) based on the initially transcribed sequence of the lacUV5 promoter known to induce a strong σ70-dependent pause [30, 33, 38].

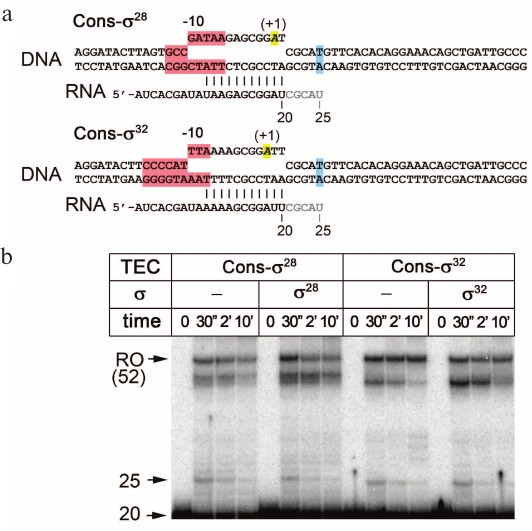

Fig. 1. Analysis of the formation of transcriptional pauses involving the σ32 and σ28 subunits. a) Structure of the TECs used in the experiments. The –10-like elements are shown in pink, the expected position of the transcription pause in blue, and the typical location of the TSS relative to –10 elements in promoters in yellow. Nucleotides added to the 3ʹ-end of starting RNA during transcription are shown in gray. b) Analysis of transcription products synthesized in the TECs depending on the presence of the σ28 and σ32 subunits. An electrophoregram of RNA products separated by 15% PAGE under denaturing conditions is shown. Positions of the starting RNA (20 nt), paused RNA (25 nt), and the full-length product (RO, 52 nt) are indicated.

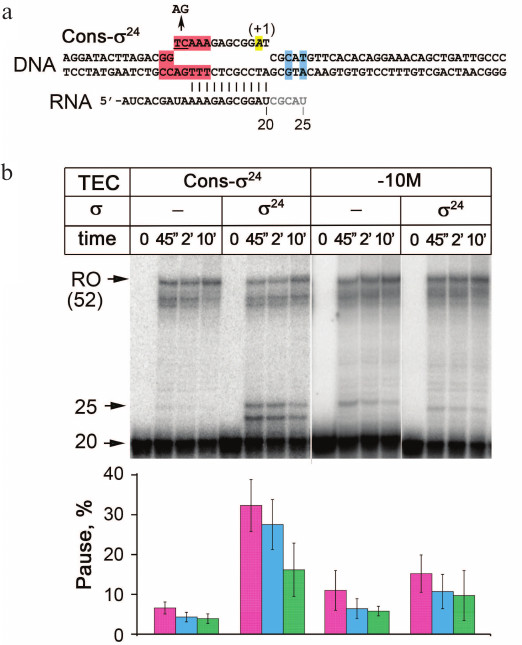

Fig. 2. Analysis of σ24-dependent transcriptional pausing. a) The TEC structure. Designations correspond to Fig. 1. b) Analysis of transcription products in the TEC containing the consensus –10-element for σ24 or –10-element with the substitution of the conserved TC dinucleotide with AG (–10M). Electrophoregram of RNA products separated by 15% PAGE is shown. Positions of the starting RNA (20 nt), paused RNA (25 nt), and the full-length product (RO, 52 nt) are indicated. The histogram shows the efficiency of pause formation (the ratio of paused RNA products to the sum of paused and read-through RNAs in percent) for each gel lane.

For TEC assembly, RNA was first annealed to the template DNA oligonucleotide, then the hybrid was incubated with core RNAP, and an excess of nontemplate DNA was added, resulting in formation of a completely functional TEC [33, 34].

Figure 1b shows the pattern of transcription products synthesized in reconstituted TECs containing consensus –10 elements for the σ32 and σ28 subunits. A major part of the starting 20 nt RNA is elongated by RNAP, thus indicating successful TEC assembly. Even in the absence of σ factors, a transcriptional pause is observed for both TECs (25 nt RNA product). This can be explained by the presence of a backtrack-inducing DNA sequence in this region [33, 41, 42, 50]. At the same time, the addition of either σ32 or σ28 subunit does not increase the pause efficiency, and the major part of active complexes efficiently transcribe through the expected pausing region and synthesize full-length 52 nt RNA product (a minor fraction of RNAs has shorter lengths possibly due to premature TEC stalling near the template end). Thus, these two σ subunits are apparently unable to induce transcriptional pausing in the studied model system.

The same approach was then used for the σ24 subunit. As shown in Fig. 2b, in the absence of σ24, pausing occurs with low efficiency and most transcription complexes synthesize full-length or near full-length products. The addition of σ24 leads to a significant increase in the amounts of 23 and 25 nt RNA products corresponding to the expected site of pause. Indeed, the calculated pausing efficiency is much higher in the presence of σ24 subunit than in its absence (~40 and 7%, respectively).

To understand the role of the –10-like element (consensus GTCAAA [49]) in pause formation, we replaced a conserved dinucleotide TC in this element with AG (TEC –10M; Fig. 3a). As shown in the figure, this TEC has a slightly increased efficiency of the pause formation in the absence of σ24. At the same time, the addition of σ24 does not increase pause formation (Fig. 3b). Thus, pause formation depends on the TC dinucleotide in the –10-like element. The role of these nucleotides can be explained from the structural point of view. Recent structural analysis of a complex of σ24 with a ssDNA oligonucleotide corresponding to the nontemplate promoter strand revealed that the TC residues in the –10 element are involved in multiple specific contacts with amino acid residues from region 2 of σ24 [51]. The same interactions are likely to participate in the pause signal recognition.

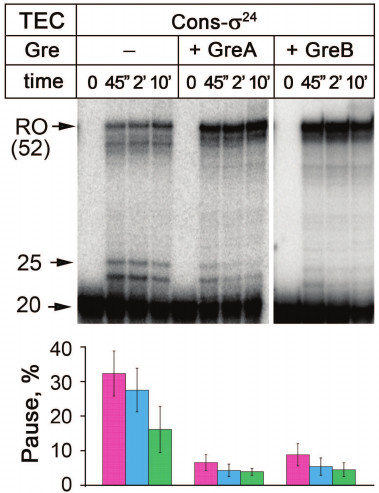

Fig. 3. Effects of Gre factors on σ24 pausing. All designations correspond to Fig. 2.

It was shown previously that during σ70- and σ38-dependent pausing, the TEC backtracks along the DNA template thus making impossible further nucleotide addition [30, 33, 38, 41, 52]. Such backtracking is stimulated by interactions of the σ subunit with DNA during pause signal recognition, while RNAP continues nucleotide addition. As a result, an unstable stressed complex is formed that can relax by backward translocation, and the RNA 3ʹ-end loses its contacts with the active site. In E. coli, such complexes can be reactivated by the transcription factors GreA and GreB, which assist RNA cleavage in the active site of RNAP [53, 54]. The Gre factors reactivate stalled TECs during σ70- and σ38-dependent pausing [30, 33, 34, 41, 52]. We tested whether these transcription factors can also affect the σ24 pause. As shown in Fig. 3, both factors, GreA and GreB, decrease the efficiency of pause formation. Thus, similarly to the other σ factors, σ24-dependent pausing is likely accompanied by TEC backtracking.

σ24 is the first member of the group 4 σ factors for which the ability to induce transcriptional pausing is shown. The properties of σ24-pause are similar to σ70- and σ38-dependent pauses investigated previously. Thus, conserved regions σ1 and σ3, which are absent in all σ group 4 members including σ24, are not crucial for pause formation. Indeed, it was shown that a fragment of σ70 lacking most of its region 1 and the whole region 4 is also able to induce σ0-dependent pausing [39]. Thus, similarly to σ70-dependent pausing, the pause formation depends on the interactions of σ24 region 2 with core RNAP and with the –10-like element in the nontemplate DNA strand [32].

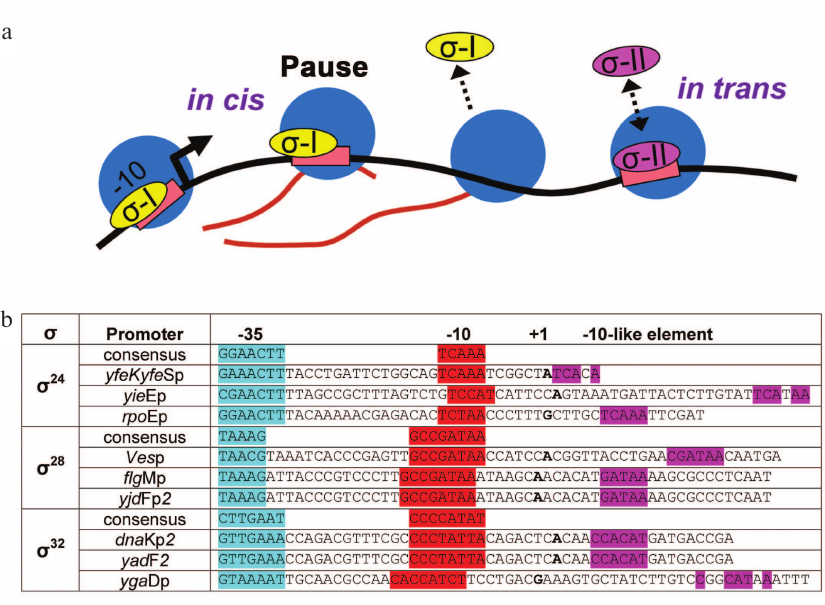

Two mechanisms of σ-dependent pausing formation were proposed previously. In the first case, the pause signal can be recognized by the same σ molecule that participated in transcription initiation and remained bound to RNAP during promoter escape (in cis mechanism; Fig. 4a) [37]. In the second case, the σ factor can bind free TEC and induce pausing in trans (Fig. 4a). In trans pause formation was shown for both σ70 and σ38 subunits [30, 31, 33, 34]. In this work, we tested only in trans pausing, by adding the σ factors to TECs carrying consensus –10 element sequences.

Fig. 4. Possible mechanisms for the formation of transcriptional pauses with the participation of alternative σ subunits. a) Formation of pauses in cis, when the pause signal is recognized in promoter-proximal region by the same σ subunit that participated in transcription initiation, and in trans, when another σ subunit binds free TEC. b) Examples of promoters containing potential σ-dependent pause signals in the initially transcribed regions. For each σ subunit, consensus sequences of –35 (turquoise) and –10 (red) elements are shown; the starting point of transcription is shown in bold.

In contrast to the σ24 subunit, σ28 and σ32 (group 3 σ factors) do not induce transcriptional pausing in this model system. The σ subunit concentrations used in this work (2.5 μM) greatly exceed previously measured dissociation constants for binding of σ70 and σ38 to the TEC (~150 and 300 nM, respectively) [34] and are comparable to or greater than intracellular concentrations of σ28 and σ32 [55, 56]. It is difficult to understand why group 3 σ factors do not induce transcriptional pausing, since no information on the structure of RNAP holoenzymes containing these alternative σ subunits is available to date. Furthermore, it is known that pausing signals for σ70-dependent pauses can include not only –10-like elements but also additional motifs such as backtrack-inducing sequence around the RNA 3′-end or –35-like element [40-42, 50]. It is possible that formation of σ28- and σ32-dependent pauses may also require additional DNA sequences that were not present in the TECs analyzed in this study.

Analysis of the ability of alternative σ subunits to induce transcriptional pausing after promoter-dependent transcription initiation is an important task for future studies. Indeed, analysis of known promoters for σ32, σ28, and σ24 reveals that some of them contain in the initially transcribed region sequences similar to the –10 element consensus for these σ subunits (Fig. 4b). Thus, σ-dependent pauses might occur by an in cis mechanism during promoter-dependent transcription if the σ subunits could remain bound to RNAP after promoter escape and recognize these sequences. It is possible that σ28- and σ32-dependent pauses may be detected in the future in such experimental systems. Furthermore, it would be interesting to investigate the influence of temperature on σ32-dependent pausing, since this subunit is responsible for transcription under heat shock conditions.

Although σ-dependent pauses were discovered long ago in bacteriophages and in several phylogenetically distant bacterial species [30, 36, 38, 57], their prevalence and functional significance in genome transcription are still unknown even for model organisms such as E. coli [44]. Up to date, there are only rough estimates that σ70-dependent pauses can occur during transcription of 10-20% of operons [43, 58]. However, many genes are transcribed with the participation of alternative σ subunits that may also induce pausing, suggesting that the frequency of such pauses may be underestimated. Indeed, it was demonstrated that the σ70 subunit can bind TEC after transcription initiation by the RNAP holoenzyme containing the σ28 subunit (Fig. 4a) [31]. As we have shown, pauses can be induced by multiple σ factors, and their exchange could increase the complexity of transcriptional pausing and potentially participate in fine tuning of gene expression.

Acknowledgements

We thank I. Artsimovich for the pVS10 plasmid, A. Oguienko for testing the σ28 activity, and anonymous reviewers for valuable comments.

Funding

This work was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (grant 16-14-10377).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest in financial or any other sphere.

REFERENCES

1.Feklistov, A., Sharon, B. D., Darst, S. A., and

Gross, C. A. (2014) Bacterial sigma factors: a historical, structural,

and genomic perspective, Annu. Rev. Microbiol., 68,

357-376.

2.Gruber, T. M., and Gross, C. A. (2003) Multiple

sigma subunits and the partitioning of bacterial transcription space,

Annu. Rev. Microbiol., 57, 441-466.

3.Paget, M. S. (2015) Bacterial sigma factors and

anti-sigma factors: structure, function and distribution,

Biomolecules, 5, 1245-1265.

4.Zhang, N., Darbari, V. C., Glyde, R., Zhang, X.,

and Buck, M. (2016) The bacterial enhancer-dependent RNA polymerase,

Biochem. J., 473, 3741-3753.

5.Lonetto, M., Gribskov, M., and Gross, C. A. (1992)

The sigma 70 family: sequence conservation and evolutionary

relationships, J. Bacteriol., 174, 3843-3849.

6.Iyer, L. M., and Aravind, L. (2012) Insights from

the architecture of the bacterial transcription apparatus, J.

Struct. Biol., 179, 299-319.

7.Maciag, A., Peano, C., Pietrelli, A., Egli, T., De

Bellis, G., and Landini, P. (2011) In vitro transcription

profiling of the sigmaS subunit of bacterial RNA polymerase:

re-definition of the sigmaS regulon and identification of

sigmaS-specific promoter sequence elements, Nucleic Acids Res.,

39, 5338-5355.

8.Liu, B., Zuo, Y., and Steitz, T. A. (2016)

Structures of E. coli sigmaS-transcription initiation complexes

provide new insights into polymerase mechanism, Proc. Natl. Acad.

Sci. USA, 113, 4051-4056.

9.White-Ziegler, C. A., Um, S., Perez, N. M., Berns,

A. L., Malhowski, A. J., and Young, S. (2008) Low temperature

(23°C) increases expression of biofilm-, cold-shock- and

RpoS-dependent genes in Escherichia coli K-12,

Microbiology, 154, 148-166.

10.Battesti, A., Majdalani, N., and Gottesman, S.

(2011) The RpoS-mediated general stress response in Escherichia

coli, Annu. Rev. Microbiol., 65, 189-213.

11.Zhao, K., Liu, M., and Burgess, R. R. (2007)

Adaptation in bacterial flagellar and motility systems: from regulon

members to "foraging"-like behavior in E. coli, Nucleic Acids

Res., 35, 4441-4452.

12.Nonaka, G., Blankschien, M., Herman, C., Gross,

C. A., and Rhodius, V. A. (2006) Regulon and promoter analysis of the

E. coli heat-shock factor, sigma32, reveals a multifaceted

cellular response to heat stress, Genes Dev., 20,

1776-1789.

13.Neidhardt, F. C., VanBogelen, R. A., and Lau, E.

T. (1983) Molecular cloning and expression of a gene that controls the

high-temperature regulon of Escherichia coli, J.

Bacteriol., 153, 597-603.

14.Grossman, A. D., Erickson, J. W., and Gross, C.

A. (1984) The htpR gene product of E. coli is a sigma factor for

heat-shock promoters, Cell, 38, 383-390.

15.Komeda, Y. (1986) Transcriptional control of

flagellar genes in Escherichia coli K-12, J. Bacteriol.,

168, 1315-1318.

16.Komeda, Y., Kutsukake, K., and Iino, T. (1980)

Definition of additional flagellar genes in Escherichia coli

K12, Genetics, 94, 277-290.

17.Arnosti, D. N., and Chamberlin, M. J. (1989)

Secondary sigma factor controls transcription of flagellar and

chemotaxis genes in Escherichia coli, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.

USA, 86, 830-834.

18.Barrios, A. F., Zuo, R., Ren, D., and Wood, T. K.

(2006) Hha, YbaJ, and OmpA regulate Escherichia coli K12 biofilm

formation and conjugation plasmids abolish motility, Biotechnol.

Bioeng., 93, 188-200.

19.Lipinska, B., Sharma, S., and Georgopoulos, C.

(1988) Sequence analysis and regulation of the htrA gene of

Escherichia coli: a sigma 32-independent mechanism of

heat-inducible transcription, Nucleic Acids Res., 16,

10053-10067.

20.Wang, Q. P., and Kaguni, J. M. (1989) A novel

sigma factor is involved in expression of the rpoH gene of

Escherichia coli, J. Bacteriol., 171,

4248-4253.

21.Rouviere, P. E., De Las Penas, A., Mecsas, J.,

Lu, C. Z., Rudd, K. E., and Gross, C. A. (1995) rpoE, the gene encoding

the second heat-shock sigma factor, sigma E, in Escherichia

coli, EMBO J., 14, 1032-1042.

22.Egler, M., Grosse, C., Grass, G., and Nies, D. H.

(2005) Role of the extracytoplasmic function protein family sigma

factor RpoE in metal resistance of Escherichia coli, J.

Bacteriol., 187, 2297-2307.

23.Angerer, A., Enz, S., Ochs, M., and Braun, V.

(1995) Transcriptional regulation of ferric citrate transport in

Escherichia coli K-12. Fecl belongs to a new subfamily of sigma

70-type factors that respond to extracytoplasmic stimuli, Mol.

Microbiol., 18, 163-174.

24.Bar-Nahum, G., and Nudler, E. (2001) Isolation

and characterization of sigma(70)-retaining transcription elongation

complexes from Escherichia coli, Cell, 106,

443-451.

25.Kapanidis, A. N., Margeat, E., Laurence, T. A.,

Doose, S., Ho, S. O., Mukhopadhyay, J., Kortkhonjia, E., Mekler, V.,

Ebright, R. H., and Weiss, S. (2005) Retention of transcription

initiation factor sigma70 in transcription elongation: single-molecule

analysis, Mol. Cell, 20, 347-356.

26.Mukhopadhyay, J., Kapanidis, A. N., Mekler, V.,

Kortkhonjia, E., Ebright, Y. W., and Ebright, R. H. (2001)

Translocation of sigma(70) with RNA polymerase during transcription:

fluorescence resonance energy transfer assay for movement relative to

DNA, Cell, 106, 453-463.

27.Mooney, R. A., Davis, S. E., Peters, J. M.,

Rowland, J. L., Ansari, A. Z., and Landick, R. (2009) Regulator

trafficking on bacterial transcription units in vivo, Mol.

Cell, 33, 97-108.

28.Raffaelle, M., Kanin, E. I., Vogt, J., Burgess,

R. R., and Ansari, A. Z. (2005) Holoenzyme switching and stochastic

release of sigma factors from RNA polymerase in vivo, Mol.

Cell, 20, 357-366.

29.Harden, T. T., Wells, C. D., Friedman, L. J.,

Landick, R., Hochschild, A., Kondev, J., and Gelles, J. (2016)

Bacterial RNA polymerase can retain sigma70 throughout transcription,

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 113, 602-607.

30.Brodolin, K., Zenkin, N., Mustaev, A., Mamaeva,

D., and Heumann, H. (2004) The sigma 70 subunit of RNA polymerase

induces lacUV5 promoter-proximal pausing of transcription, Nat.

Struct. Mol. Biol., 11, 551-557.

31.Goldman, S. R., Nair, N. U., Wells, C. D.,

Nickels, B. E., and Hochschild, A. (2015) The primary sigma factor in

Escherichia coli can access the transcription elongation complex

from solution in vivo, eLife, 4, e10514.

32.Mooney, R. A., Darst, S. A., and Landick, R.

(2005) Sigma and RNA polymerase: an on-again, off-again relationship?

Mol. Cell, 20, 335-345.

33.Zhilina, E., Esyunina, D., Brodolin, K., and

Kulbachinskiy, A. (2012) Structural transitions in the transcription

elongation complexes of bacterial RNA polymerase during sigma-dependent

pausing, Nucleic Acids Res., 40, 3078-3091.

34.Petushkov, I., Esyunina, D., and Kulbachinskiy,

A. (2017) Sigma38-dependent promoter-proximal pausing by bacterial RNA

polymerase, Nucleic Acids Res., 45, 3006-3016.

35.Perdue, S. A., and Roberts, J. W. (2011)

Sigma(70)-dependent transcription pausing in Escherichia coli,

J. Mol. Biol., 412, 782-792.

36.Ring, B. Z., Yarnell, W. S., and Roberts, J. W.

(1996) Function of E. coli RNA polymerase sigma factor sigma 70

in promoter-proximal pausing, Cell, 86, 485-493.

37.Marr, M. T., Datwyler, S. A., Meares, C. F., and

Roberts, J. W. (2001) Restructuring of an RNA polymerase holoenzyme

elongation complex by lambdoid phage Q proteins, Proc. Natl. Acad.

Sci. USA, 98, 8972-8978.

38.Nickels, B. E., Mukhopadhyay, J., Garrity, S. J.,

Ebright, R. H., and Hochschild, A. (2004) The sigma 70 subunit of RNA

polymerase mediates a promoter-proximal pause at the lac promoter,

Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol., 11, 544-550.

39.Zenkin, N., Kulbachinskiy, A., Yuzenkova, Y.,

Mustaev, A., Bass, I., Severinov, K., and Brodolin, K. (2007) Region

1.2 of the RNA polymerase sigma subunit controls recognition of the

–10 promoter element, EMBO J., 26, 955-964.

40.Devi, P. G., Campbell, E. A., Darst, S. A., and

Nickels, B. E. (2010) Utilization of variably spaced promoter-like

elements by the bacterial RNA polymerase holoenzyme during early

elongation, Mol. Microbiol., 75, 607-622.

41.Perdue, S. A., and Roberts, J. W. (2010) A

backtrack-inducing sequence is an essential component of Escherichia

coli sigma(70)-dependent promoter-proximal pausing, Mol.

Microbiol., 78, 636-650.

42.Strobel, E. J., and Roberts, J. W. (2014)

Regulation of promoter-proximal transcription elongation: enhanced DNA

scrunching drives lambdaQ antiterminator-dependent escape from a

sigma70-dependent pause, Nucleic Acids Res., 42,

5097-5108.

43.Deighan, P., Pukhrambam, C., Nickels, B. E., and

Hochschild, A. (2011) Initial transcribed region sequences influence

the composition and functional properties of the bacterial elongation

complex, Genes Dev., 25, 77-88.

44.Petushkov, I., Esyunina, D., and Kulbachinskiy,

A. (2017) Possible roles of sigma-dependent RNA polymerase pausing in

transcription regulation, RNA Biol., 14, 1678-1682.

45.Svetlov, V., and Artsimovitch, I. (2015)

Purification of bacterial RNA polymerase: tools and protocols,

Methods Mol. Biol., 1276, 13-29.

46.Pupov, D., Kuzin, I., Bass, I., and

Kulbachinskiy, A. (2014) Distinct functions of the RNA polymerase sigma

subunit region 3.2 in RNA priming and promoter escape, Nucleic Acids

Res., 42, 4494-4504.

47.Anthony, L. C., Foley, K. M., Thompson, N. E.,

and Burgess, R. R. (2003) Expression, purification of, and monoclonal

antibodies to sigma factors from Escherichia coli, Methods

Enzymol., 370, 181-192.

48.Laptenko, O., and Borukhov, S. (2003) Biochemical

assays of Gre factors of Thermus thermophilus, Methods

Enzymol., 371, 219-232.

49.Rhodius, V. A., Suh, W. C., Nonaka, G., West, J.,

and Gross, C. A. (2006) Conserved and variable functions of the sigmaE

stress response in related genomes, PLoS Biol., 4,

e2.

50.Strobel, E. J., and Roberts, J. W. (2015) Two

transcription pause elements underlie a sigma70-dependent pause cycle,

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 112, E4374-4380.

51.Campagne, S., Marsh, M. E., Capitani, G.,

Vorholt, J. A., and Allain, F. H. (2014) Structural basis for –10

promoter element melting by environmentally induced sigma factors,

Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol., 21, 269-276.

52.Marr, M. T., and Roberts, J. W. (2000) Function

of transcription cleavage factors GreA and GreB at a regulatory pause

site, Mol. Cell, 6, 1275-1285.

53.Borukhov, S., Sagitov, V., and Goldfarb, A.

(1993) Transcript cleavage factors from E. coli, Cell,

72, 459-466.

54.Laptenko, O., Lee, J., Lomakin, I., and Borukhov,

S. (2003) Transcript cleavage factors GreA and GreB act as transient

catalytic components of RNA polymerase, EMBO J., 22,

6322-6334.

55.Grigorova, I. L., Phleger, N. J., Mutalik, V. K.,

and Gross, C. A. (2006) Insights into transcriptional regulation and

sigma competition from an equilibrium model of RNA polymerase binding

to DNA, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 103, 5332-5337.

56.Jishage, M., Iwata, A., Ueda, S., and Ishihama,

A. (1996) Regulation of RNA polymerase sigma subunit synthesis in

Escherichia coli: intracellular levels of four species of sigma

subunit under various growth conditions, J. Bacteriol.,

178, 5447-5451.

57.Zhilina, E., Miropolskaya, N., Bass, I.,

Brodolin, K., and Kulbachinskiy, A. (2011) Characteristics of

sigma-dependent pausing in RNA polymerases from E. coli and

T. aquaticus, Biochemistry (Moscow), 76,

1348-1358.

58.Hatoum, A., and Roberts, J. (2008) Prevalence of

RNA polymerase stalling at Escherichia coli promoters after open

complex formation, Mol. Microbiol., 68, 17-28.