Characterization of a Transposon Tn5-Generated Mutant of Yersinia pestis Defective in Lipooligosaccharide Biosynthesis

R. Z. Shaikhutdinova1, S. A. Ivanov1, S. V. Dentovskaya1,a,b*, G. M. Titareva1, and Yu. A. Knirel2,c,d

1State Research Center for Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 142279 Obolensk, Moscow Region, Russia2Zelinsky Institute of Organic Chemistry, Russian Academy of Sciences, 119991 Moscow, Russia

* To whom correspondence should be addressed.

Received September 7, 2018; Revised October 25, 2018; Accepted October 25, 2018

To identify Yersinia pestis genes involved in the microbe’s resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides, the strategy of random transposon mutagenesis with a Tn5 minitransposon was used, and the library was screened for detecting polymyxin B (PMB) susceptible mutants. The mutation responsible for PMB-sensitive phenotype and the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) structure were characterized for the Y. pestis strain KM218-A3. In this strain the mini-Tn5 was located in an open reading frame with the product homologous to the E. coli protein GmhB (82% identity) functioning as d-glycero-d-manno-heptose-1,7-diphosphate phosphatase. ESI FT ICR mass spectrometry of anions was used to study the structure of the unmodified LPS of Y. pestis KM218-A3, and molecules were revealed with the full-size LPS core or with two types of an incomplete core: consisting of Kdo-Kdo or Ko-Kdo disaccharides and Hep-(Kdo)-Kdo or Hep-(Ko)-Kdo trisaccharides. The performed complementation confirmed that the defect in the biological properties of the mutant strain was caused by inactivation of the gmhB gene. These findings indicated that the gmhB gene product of Y. pestis is essential for production of wild-type LPS resistant to antimicrobial peptides and serum.

KEY WORDS: Yersinia pestis, lipopolysaccharide, heptose biosynthesis, serum resistance, antibiotic resistanceDOI: 10.1134/S0006297919040072

Abbreviations: Ara4N, 4-amino-4-deoxy-l-arabinose; CAMP, cationic antimicrobial peptides; CFU, colony-forming unit; ESI FT ICR, high resolution electrospray ionization Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry; Glc, glucose; GlcNAc, N-acetylglucosamine; Hep, l-glycero- d -manno-heptose; Kdo, 3-deoxy-d-manno-oct-2-ulosonic acid; Ko, d-glycero-d-talo-oct-2-ulosonic acid; LPS, lipopolysaccharides; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; NHS, normal human serum; PMB, polymyxin B; HIS, heat-inactivated serum (incubated at 56°C for 30 min to inactivate complement).

The pathogenicity of Y. pestis in the body of a susceptible host

can be realized if the causative agent of plague possesses pathogenic

factors with different functional direction that would protect it

against the innate and acquired immunity of the macroorganism. The more

ancient evolutionary innate immunity system acts immediately after the

inculcation of a pathogen and activates phagocytosis and inflammatory

reactions. In the inflammatory reactions a great role belongs to the

complement system, cytokines, lysozyme, properdin, leucine, and

β-lysine, as well as to other antimicrobial agents including

cationic peptides. During the evolution of interrelationships of the

micro- and macroorganism, resistance mechanisms to the innate immunity

factors were formed in bacterial pathogens, in particular, in

pathogenic yersiniaе that allow them to survive and multiply in

the body of a susceptible host [1-3]. The resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides

(CAMP) found in many tissues of mammals and insects [4-6] is an important factor of

Y. pestis pathogenicity [7, 8]. This publication considers determination of new

genes whose products allow Y. pestis to escape the bactericidal

action of cationic peptide antibiotics. To obtain Y. pestis

strains susceptible to polymyxin B (PMB) as a representative of such

antibiotics, we have chosen a strategy of random transposon mutagenesis

with the minitransposon Tn5.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

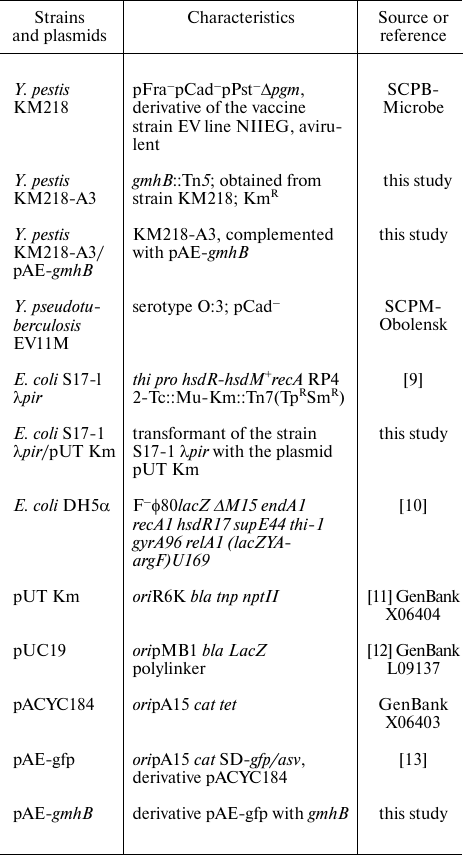

Bacterial strains and plasmids. Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this work were obtained from the State Collection of Pathogenic Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (SCPM-Obolensk). Their characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Bacterial strains and plasmids used

in this study

Growing the bacteria. The Y. pestis strain for mutagenesis was grown at temperature 25°C for 48 h on a solid nutrient medium Brain heart infusion (HiMedia, India) [14] supplemented with hemolyzed blood to 2% (v/v) at pH 7.2. The Escherichia coli strain S17-1 λpir and its derivatives were grown at temperature 37°C for 24 h in Luria–Bertani medium [15] at pH 7.2. For isolating lipopolysaccharides (LPS), the Y. pestis strains were grown at temperature 25°C as described earlier [16].

Insertion mutagenesis. Insertion mutants were obtained using a conjugation method [17]. As a recipient, we used the Y. pestis strain KM218 resistant to PMB and as a donor we used the E. coli strain S17 λpir containing the plasmid pUTKm [11]. Yersinia pestis conjugants were counter-selected on media containing gentian violet (1 : 100,000) (w/v) (DIAEM, Russia) supplemented with kanamycin (40 μg/ml) or ampicillin (100 μg/ml).

Gene engineering. Chromosomal DNA of bacteria and DNA of plasmids were isolated as recommended by the producer, using a Genomic DNA Purification Kit and a DNA Extraction Kit (Fermentas, Lithuania). The restriction and ligation were performed using standard methods [15]. The E. coli cells were transformed by electroporation using the method described in the Operating Manual to the Electroporator 2510 device (Eppendorf, Germany).

DNA sequencing was performed by Syntol (Russia). The resulting nucleotide sequences were analyzed using the BLAST2 program on the NCBI server.

Complementation. For complementation, a low-copy expressing vector pAE-gfp was constructed. To do this, the gene gfp/asv including the SD-sequence from the plasmid pKK214GFP/ASV [18] was cloned in the pBluescript II SK(–) vector by the restriction sites PstI and EcoRI. The SmaI-SalI fragment of the resulting plasmid pBlu-gfp was cloned into the plasmid pACYC184 by the sites EcoRV-SalI. On constructing the plasmid for complementation, the gene gfp/asv from pAE-gfp [13] was cut by the restriction sites NdeI-SalI and replaced by the coding sequence of the gmhB gene amplified with the primers GmhBNdeI (5′-TTGATGCATATGGTGACTCAGTCCGTT-3′) and GmhBSalI (5′-CTTGTCGACCTATTTATAACGCGC-3′) (Syntol).

Isolation of LPS and SDS-PAGE. LPS was isolated from dry bacterial cells with a mixture of phenol, chloroform, and petroleum ether [19] and purified by sequential enzymatic degradation of nucleic acids and proteins and repeated ultracentrifugation (105,000g, 4 h) [16].

For screening of polymyxin-sensitive clones, LPS was isolated by the method of Hitchcock and Brown [20]. SDS-PAGE was performed as described earlier [21]. To visualize LPS, the gel was stained with ammonia silver oxide solution after oxidation with periodic acid as recommended by Tsai and Frash [22].

Mass spectrometry. The structures of the LPS components were established using high resolution electrospray ionization Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry (ESI FT ICR). The mass spectra were taken with recording anions using an ApexII device (Bruker Daltonics, USA) as described earlier [16].

Minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of PMB was determined using the routine approach of dilution in liquid nutrient medium [23].

Study on Y. pestis interactions with serum. Bactericidal properties of serum were determined using a slight modification of the method of Barnes et al. [24]. Viability of the studied strains after cultivation in normal human serum with intact complement (NHS) or with heat-inactivated complement (HIS) was determined after planting onto dense nutrient medium.

RESULTS

Obtaining mini-Tn5 mutants sensitive to PMB. The genes responsible for the resistance of the plague microbe to PMB were determined using random transposon mutagenesis. This method allowed us to obtain a large number of mutant clones due to inserting of the minitransposon Tn5 encoding kanamycin resistance into genome of the recipient strain. As a recipient, we used a plasmid-free derivative of the Y. pestis vaccine strain EV line NIIEG, KM218, that was resistant to the bactericidal action of PMB and human serum. The structure of LPS from this strain was determined by us earlier [16].

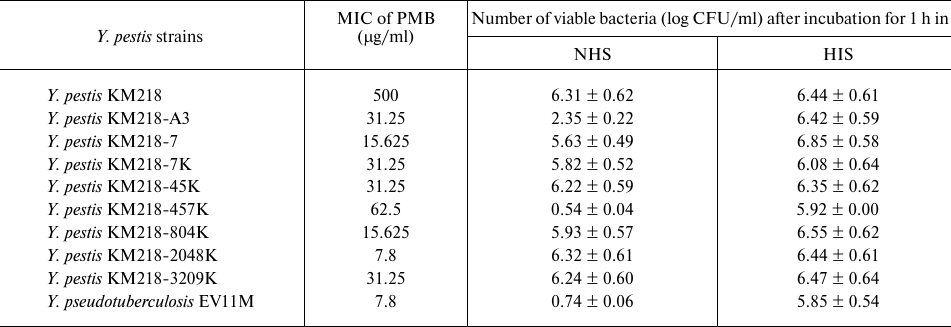

In total, in five separate experiments with mutagenesis we obtained more than 3000 clones of Y. pestis KM218 with the minitransposon Tn5 inserted into a chromosome, and among these clones eight isolates were detected with the phenotype PolS. These mutants were denominated as KM218-A3, KM218-7, KM218-7K, KM218-45K, KM218-457K, KM218-804K, KM218-2048K, and KM218-3209K. The MIC of PMB for the sensitive mutants was 20-250 times lower than the MIC for the Y. pestis parent strain KM218 (Table 2). Two of the eight clones (KM218-457K and KM218-A3) were sensitive also to the bactericidal activity of the normal human serum complement. After incubation for 1 h in NHS, the number of colony-forming units (CFU) was significantly lower than after incubation in serum containing the heat-inactivated complement. The Y. pseudotuberculosis strain EV11M with the core part of the LPS completely lacking heptose residues [16] displayed a high sensitivity to PMB and NHS.

Table 2. Sensitivity of Yersinia

strains to PMB and NHS

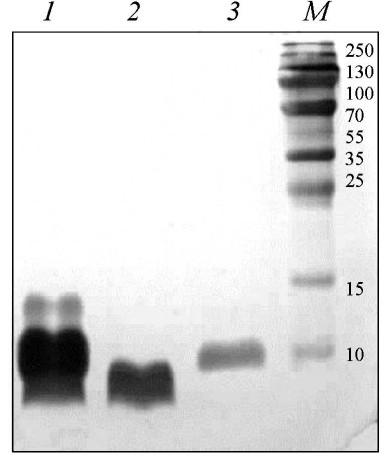

The analysis by SDS-PAGE revealed that the migration rates of LPS of PMB-sensitive isolates were not different from the migration rate of the parent strain Y. pestis KM218. The migration rate of LPS of the mutant strain KM218-457K was higher (data not presented). LPS from the mutant strain KM218-A3 formed in the polyacrylamide gel two bands, one of which had the same migration rate as LPS of the initial strain KM218 (Fig. 1) and the other was on the level of LPS isolated from the strain Y. pseudotuberculosis EV11M whose core was shown by us to completely lack heptose residues [16]. The structure of LPS of y. pestis KM218-A3 and the mutation responsible for this phenotype were characterized later.

Fig. 1. SDS-PAGE of LPS preparations from the Y. pestis strains KM218-A3, KM218-A3/pAE-gmhB, and Y. pseudotuberculosis EV11M isolated by the method of Hitchcock and Brown [17]. Lanes: 1) Y. pestis KM218-A3; 2) Y. pseudotuberculosis EV11M; 3) Y. pestis KM218-A3/pAE-gmhB; M) kit of standard proteins (Protein Molecular Weight Marker; Fermentas, Lithuania).

Determination of the location of minitransposon Tn5 in strain KM218-A3. The genomic DNA isolated from mutant KM218-A3 was hydrolyzed with restrictases BamHI and BglII and ligated with plasmid pUC19 hydrolyzed by the site BamHI. The resulting ligase mixture was used for transformation of E. coli DH5α competent cells, and clones resistant to ampicillin (the plasmid marker) and kanamycin (the mini-Tn5 marker) were selected. Plasmids isolated from the resulting clones included insertions of ~1800 and 5000 bp that presented the DNA sequence of y. pestis flanking the mini-Tn5 insertion and 900 bp DNA of mini-Tn5. To determine the nucleotide sequence of the plague microbe in the region of the inserted transposon, both chains of the DNA insertion were sequenced. The resulting nucleotide sequences were compared to the DataBank NCBI (https://www.ncbi) using the BLAST2 program. It was established that in the strain y. pestis KM218-A3 the mini-Tn5 was located at the beginning of the open reading frame YPO1074 (NC_003143.1, 1216470-1217036). The product of this gene was 82% identical with protein GmhB of E. coli (WP_001608862.1) that functions as d-glycero-d-manno-heptose-1,7-diphosphate phosphatase [25].

Complementation of the Tn5-mutation in the y. pestis strain KM218-A3. To confirm that the obtained defect of biological properties of the mutant strain was caused by inactivation of the corresponding gene, an intact gene gmhB was cloned in the constructed expressing vector pACYC-gfp. The resulting plasmid pAE-gmhB was inserted by electroporation into the y. pestis strain KM218-A3. The electrophoretic profile of the LPS preparation isolated from the complemented strain y. pestis KM218-A3/pAE-gmhB was similar to the initial strain y. pestis KM218, and this confirmed that the cloned gene gmhB successfully complemented the created mutation (Fig. 1).

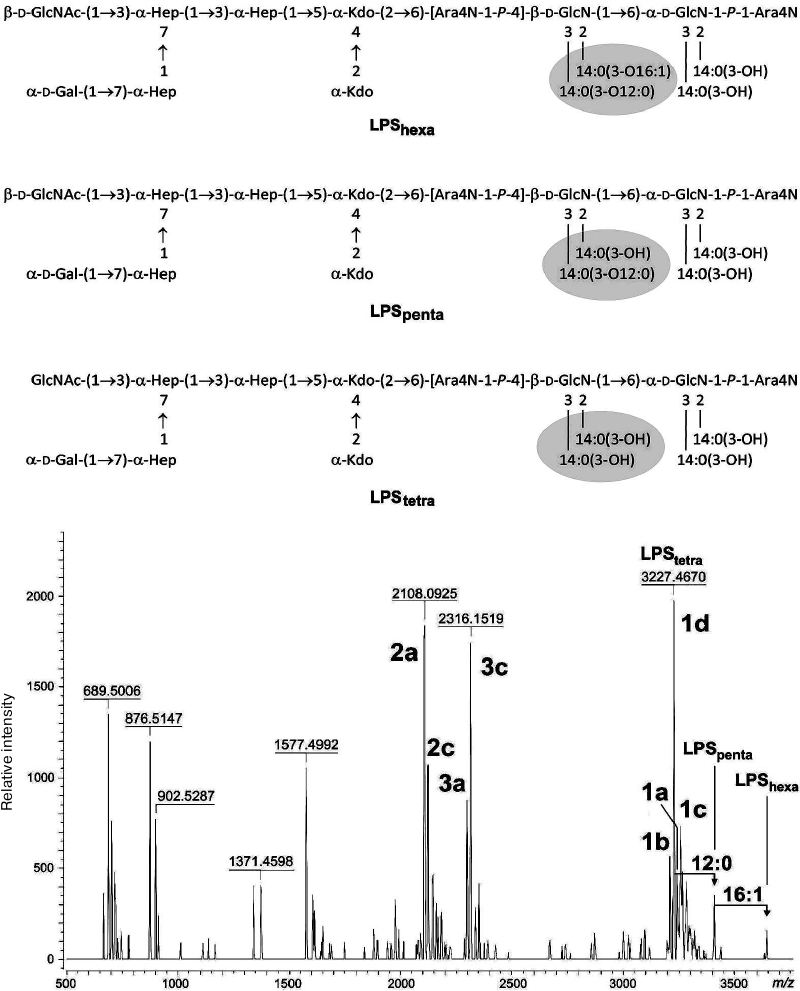

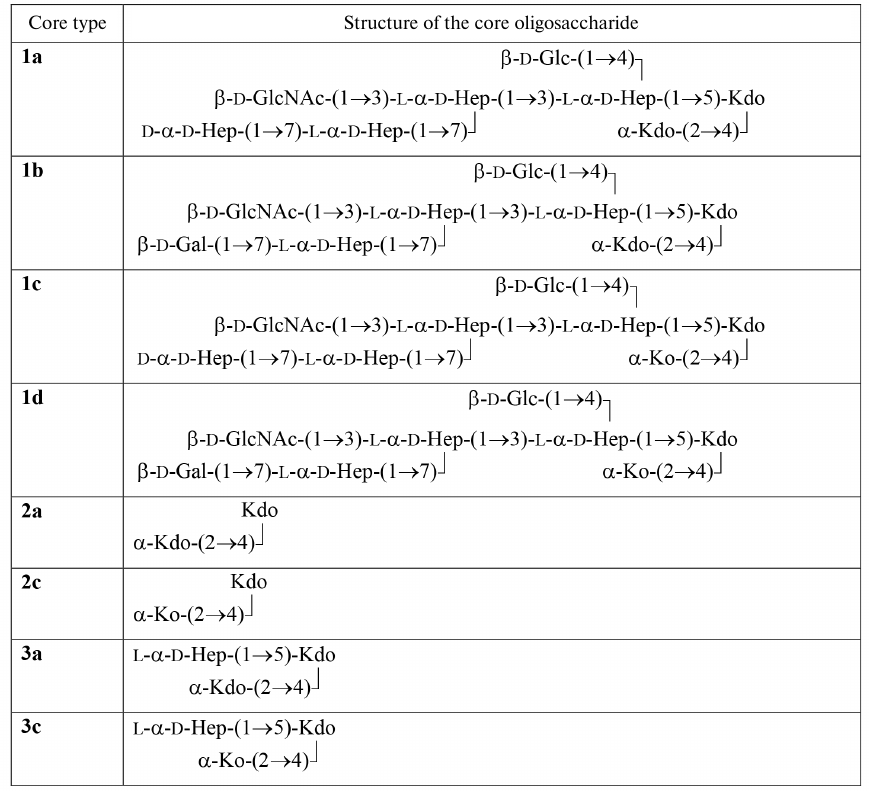

Structural characteristic of LPS from y. pestis strain KM218-A3. The ESI FT ICR mass spectrum of the unmodified LPS obtained from the KM218-A3 strain grown at 25°C (Fig. 2) contained the major peak at m/z 3227.4670 corresponding to the lipid A tetracyl form with two 4-amino-4-deoxy-l-arabinose (Ara4N) residues and the 1d type core with the stoichiometric content of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) (Fig. 2). GlcNAc was identified by us earlier in the LPS of the “wild” strain KM218 [16]. The minor components corresponded to compounds with the 1a-1c type cores differed from 1d by replacement of d-glycero-d-talo-oct-2-ulosonic acid (Ko) by 3-deoxy-d-manno-oct-2-ulosonic acid (Kdo) and/or of Gal by d-glycero-d-manno-heptose (dd-Hep) (Table 3). Moreover, they contained one or two additional C12:0 and C16:1 fatty acid residues, respectively (Fig. 2). A small number of molecules included one Ara4N residue in the lipid A.

Fig. 2. ESI ICR FT mass spectrum of anions derived from the unmodified LPS of Y. pestis strain KM218-A3 grown at temperature 25°C. Above the spectrum, the structures of hexacyl (LPShexa), pentacyl (LPSpenta), and tetracyl (LPStetra) forms of the LPS are shown. Ara4N, 4-amino-4-deoxy-l-arabinose; Hep, l-glycero- d -manno-heptose; Kdo, 3-deoxy-d-manno-oct-2-ulosonic acid; 14:0(3-OH), (R)-3-hydroxymyristic acid; 14:0(3-O12:0), (R)-3-lauroyloxymyristic acid; 14:0(3-O16:1), (R)-3-palmitoleoyloxymyristic acid; P, phosphate group.

Table 3. Types of core oligosaccharides in

mutant strain y. pestis KM218-A3

The ESI ICR FT mass spectrum revealed molecules with an incomplete core of two types. One of them was represented by Kdo-Kdo (2a, major form) and Ko-Kdo (2c, minor component) disaccharides, and the other – by Hep-(Kdo)-Kdo (3a, minor component) and Hep-(Ko)-Kdo (3c, major form) trisaccharides (Fig. 2).

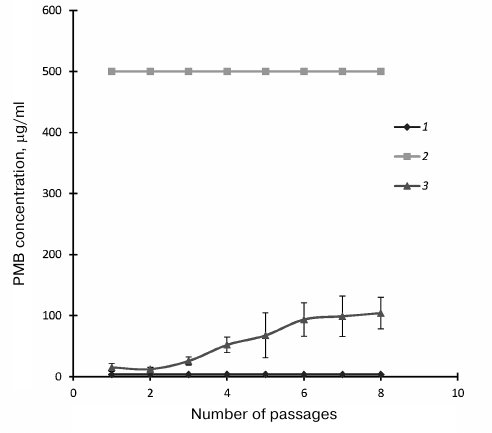

Sensitivity of y. pestis strain KM218-A3 to PMB. On everyday successive replanting of the studied strain KM218-A3, the MIC of PMB increased (31.25-125 μg/ml), not reaching the MIC value of the parental strain (Fig. 3). However, despite the replanting, the strain remained sensitive to the bactericidal action of the NHS complement.

Fig. 3. Dependence of Yersinia PMB MIC on number of passages on solid nutrient medium: 1) Y. pseudotuberculosis EV11M; 2) Y. pestis KM218; 3) Y. pestis KM218-A3.

DISCUSSION

The ability of Y. pestis for intracellular reproduction and its resistance to the bactericidal action of cationic antimicrobial peptides and human serum complement play an important role in the pathogenesis of plague [7, 26-30]. It is established that the Y. pestis resistance to bactericidal action of cationic peptides is higher than the resistance of Y. pseudotuberculosis and Y. enterocolitica. The increase in the resistance correlated with the increase in the reduction degree of LPS. The complete absence in the Y. pestis LPS structure of negatively charged O-polysaccharide chains resulted in the minimum ability of the bacteria to sorb cationic peptides [31]. Our data have confirmed that the strain Y. pestis subsp. pestis KM218 is highly resistant to PMB at temperature 25°C [7]. In the present study, we have obtained PMB-sensitive mutants of the strain Y. pestis KM218 and detected a genetic locus involved in providing the resistance to this antimicrobial agent.

It was shown earlier by us, as well as by other researchers, that mutations damaging the structure of oligosaccharide core or of lipid A in representatives of the Yersinia genus led to decrease in the resistance of the strains to PMB, β-defensins, cathelicidins, and cecropins [32-39]. It has been shown that in several bacteria, the region of LPS inner core is a bacteriophage receptor necessary to withstand the damaging action of human serum component and for resistance against opsonization and capture by neutrophils [39-42]. In the present study, we have established that in the PMB-sensitive strain y. pestis KM218-A3 mini-Tn5 is located in the beginning of the open reading frame YPO1074 (NC_003143.1, 1216470-1217036). The product of this gene was necessary also for resistance of the y. pestis strain to the human serum complement.

The function of the y. pestis YPO1074 gene product was assumed based on the homology determined by BLAST search. The product of the open reading frame YPO1074 of Y. pestis shares 82% identity to GmhB (d-glycero-d-manno-heptose-1,7-diphosphate phosphatase) of E. coli (earlier YaeD), which converts d-glycero-d-manno-heptose 1,7-diphosphate into d-glycero-d-manno-heptose 1-phosphate. This reaction is a stage of biosynthesis of ADP-l-glycero-d-manno-heptose, which is a substrate for WaaC and WaaF heptosyltransferases in E. coli and other gram-negative microorganisms [25]. The pathway of ADP-l-glycero-d-manno-heptose biosynthesis and the genes participating in this pathway were described in detail earlier [25, 43]. Thus, the gene YPO1074 was identified as gmhB and named respectively.

According to the findings, LPS of Y. pestis strain KM218 with mutation in the gmhB gene contained several type molecules of the oligosaccharide core: the full-size molecules characteristic for the initial strain KM218 and molecules with the core reduced to disaccharide (Kdo-Kdo or Ko-Kdo) and trisaccharide (Hep-(Kdo)-Kdo or Hep-(Ko)-Kdo). The core represented by disaccharides of Kdo and Ko was detected by us earlier on the determination of structure of LPS of the highly sensitive to PMB laboratory strain Y. pseudotuberculosis EV11M [16].

Kneidinger et al. [25] showed that the deletion in the gmhB gene in E. coli strain K-12 led to disorder in the LPS core biosynthesis manifesting in appearance of molecules with heptose residues and without them. They supposed that these different molecules could indicate a partial compensation of the affected synthesis of ADP-l-glycero-d-manno-heptose and found that such compensation was due to the bifunctional protein HisB of E. coli, which also displayed histidinol phosphate phosphatase activity. In the case of the y. pestis mutant KM218-A3, the different degree reduction of the LPS core molecules and the detected insignificant growth of the PMB-resistance in the process of replanting seemed to be also associated with compensatory mechanisms. However, in spite of this, the strain retained the sensitivity to PMB, not reaching the MIC value of the highly resistant parental strain. Moreover, the strain KM218-A3 retained the sensitivity to NHS, not depending on the replanting.

Thus, this study on strain y. pestis KM218-A3 obtained by random transposon mutagenesis with the minitransposon Tn5 has shown that the change of the YPO1074 gene whose product is involved in a stage of ADP-l-glycero-d-manno-heptose synthesis affects synthesis of the pentasaccharide fragment of LPS. This leads to appearance of LPS molecules with shortened core and to sensitivity of the plague microbe to the bactericidal activity of normal human serum and PMB. We showed earlier that knockout mutants of Y. pestis with two or fewer monosaccharides in the LPS core were not only sensitive to CAMP and NHS but were avirulent on subcutaneous infecting mice and guinea pigs. This finding has confirmed that the LPS structure plays a key role in plague-caused lethality and that gene gmhB, alongside with the waaC, hldE and waaA genes found by us earlier [39], or the protein encoded by the gmhB gene may be considered a potential candidate for the role of molecular target for specific inhibitors of Y. pestis virulence.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Buko Lindner (Borstel’s Research Center, Germany) for help in taking the mass spectra.

Funding

This work was performed as part of the sectoral research program of Rospotrebnadzor for 2016-2020: “Problem-oriented research in the field of epidemiological surveillance of infectious and parasitic diseases”.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not include research carried out by the authors with the participation of people or animals.

REFERENCES

1.Anisimov, A. P. (2002) Factors of Yersinia

pestis providing the circulation and retention of the plague agent

in ecosystems of natural communities. Communication 1, Mol.

Genet., 3, 3-23.

2.Anisimov, A. P. (2002) Factors of Yersinia

pestis providing the circulation and retention of the plague agent

in ecosystems of natural communities. Communication 2, Mol.

Genet., 4, 3-11.

3.Portnoy, D. A. (2005) Manipulation of innate

immunity by bacterial pathogens, Curr. Opin. Immunol.,

17, 25-28.

4.Boman, H. G. (2002) Our endogenous peptide

antibiotics keep us healthy, Lakartidningen, 99,

3424-3428.

5.Yoshio, H., Tollin, M., Gudmundsson, G. H.,

Lagercrantz, H., Jornvall, H., Marchini, G., and Agerberth, B. (2003)

Antimicrobial polypeptides of human vernix caseosa and amniotic fluid:

implications for newborn innate defense, Pediatr. Res.,

53, 211-216.

6.Dimopoulos, G. (2003) Insect immunity and its

implication in mosquito–malaria interactions, Cell

Microbiol., 5, 3-14.

7.Anisimov, A. P., Dentovskaya, S. V., Titareva, G.

M., Bakhteeva, I. V., Shaikhutdinova, R. Z., Balakhonov, S. V.,

Lindner, B., Kocharova, N. A., Senchenkova, S. N., Holst, O., Pier, G.

B., and Knirel, Y. A. (2005) Intraspecies and temperature-dependent

variation in susceptibility of Yersinia pestis to bactericidal

action of serum and polymyxin B, Infect. Immun., 73,

7324-7331.

8.Rebeil, R., Ernst, R. K., Gowen, B. B., Miller, S.

I., and Hinnebusch, B. J. (2004) Variation in lipid A structure

pathogenic yersiniae, Mol. Microbiol., 52, 1363-1373.

9.Simon, R., Priefer, U., and Pulher, A. (1983) A

broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic

engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram-negative bacteria,

Biotechnology, 1, 784-791.

10.Woodcock, D., Crowther, P., Doherty, J.,

Jefferson, S., DeCruz, E., Noyer-Weidner, M., Smith, S. S., Michael, M.

Z., and Graham, M. W. (1989) Quantitative evaluation of Escherichia

coli host strains for tolerance to cytosine methylation in plasmid

and phage recombinants, Nucleic Acids Res., 17,

3469-3478.

11.Herrero, M., De Lorenzo, V., and Timmis, K. N.

(1990) Transposon vectors containing non-antibiotic resistance

selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of

foreign genes in gram-negative bacteria, J. Bacteriol.,

172, 6557-6567.

12.Norrander, J., Kempe, T., and Messing, J. (1983)

Construction of improved M13 vectors using

oligodeoxynucleotide-directed mutagenesis, Gene, 26,

101-106.

13.Dentovskaya, S. V. (2012) Molecular Genetic

Mechanisms of Formation and Functional Significance of

Lipopolysaccharide of Yersinia pestis: Diss. Doct. Med. [in

Russian], MNIIEM, Moscow.

14.Ajello, L., Georg, L., Kaplan, W., and Kaufman,

L. (1963) CDC Laboratory Manual for Medical Mycology, PHS

Publication No. 994, U. S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.

C.

15.Maniatis, T., Fritsch, E. F., and Sambrook, J.

(1982) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, Cold Spring

Harbor, New York.

16.Knirel, Y. A., Lindner, B., Vinogradov, E. V.,

Kocharova, N. A., Senchenkova, S. N., Shaikhutdinova, R. Z.,

Dentovskaya, S. V., Fursova, N. K., Bakhteeva, I. V., Titareva, G. M.,

Balakhonov, S. V., Holst, O., Gremyakova, T. A., Pier, G. B., and

Anisimov, A. P. (2005) Temperature-dependent variations and

intraspecies diversity of the structure of the lipopolysaccharide of

Yersinia pestis, Biochemistry, 45, 1731-1743.

17.Kokushkin, A. M. (1983) Transforming Activity

of the Plague Microbe Plasmids: Diss. Cand. Med. [in Russian],

RosNIPChI Mikrob, Saratov.

18.Abd, H., Johansson, T., Golovliov, I., Sandstrom,

G., and Forsman, M. (2003) Survival and growth of Francisella

tularensis in Acanthamoeba castellanii, Appl. Environ.

Microbiol., 69, 600-606.

19.Galanos, C., Luderitz, O., and Westphal, O.

(1969) A new method for the extraction of R lipopolysaccharides,

Eur. J. Biochem., 9, 245-249.

20.Hitchcock, P. J., and Brown, T. M. (1983)

Preparation of proteinase K-treated cell lysates for SDS-PAGE, J.

Bacteriol., 154, 269-277.

21.Prior, J. L., Hitchen, P. G., Williamson, E. D.,

Reason, A. J., Morris, H. R., Dell, A., Wren, B. W., and Titball, R. W.

(2001) Characterization of the lipopolysaccharide of Yersinia

pestis, Microb. Pathog., 30, 49-57.

22.Tsai, C. M., and Frash, C. E. (1982) A sensitive

silverstain for detecting lipopolysaccharides in polyacrylamide gels,

Anal. Biochem., 119, 115-119.

23.Hitchen, P. G., Prior, J. L., Oyston, P. C.,

Panico, M., Wren, B. W., Titball, R. W., Morris, H. R., and Dell, A.

(2002) Structural characterization of lipooligosaccharide (LOS) from

Yersinia pestis: regulation of LOS structure by the PhoPQ

system, Mol. Microbiol., 44, 1637-1650.

24.Barnes, M. G., and Weiss, A. A. (2001) BrkA

protein of Bordetella pertussis inhibits the classical pathway

of complement after C1 deposition, Infect. Immun., 69,

3067-3072.

25.Kneidinger, B., Marolda, C., Graninger, M.,

Zamyatina, A., McArthur, F., Kosma, P., Valvano, M. A., and Messner, P.

(2002) Biosynthesis pathway of

ADP-L-glycero-beta-D-manno-heptose in Escherichia

coli, J. Bacteriol., 184, 363-369.

26.Cavanaugh, D. C., and Randall, R. (1959) The role

of multiplication of Pasteurella pestis in mononuclear

phagocytes in the pathogenesis of fleaborne plague, J. Immunol.,

83, 348-371.

27.Janssen, W. A., and Surgalla, M. J. (1969) Plague

bacillus: survival within host phagocytes, Science, 163,

950-952.

28.Straley, S. C., and Harmon, P. A. (1984) Growth

in mouse peritoneal macrophages of Yersinia pestis lacking

established virulence determinants, Infect. Immun., 45,

649-654.

29.Charnetzky, W. T., and Shuford, W. W. (1985)

Survival and growth of Yersinia pestis within macrophages and an

effect of the loss of the 47-megadalton plasmid on growth in

macrophages, Infect. Immun., 47, 234-241.

30.Pujol, C., Grabenstein, J. P., Perry, R. D., and

Bliska, J. B. (2005) Replication of Yersinia pestis in

interferon-gamma-activated macrophages requires ripA, a gene

encoded in the pigmentation locus, PNAS, 102,

12909-12914.

31.Bengoechea, J. A., Diaz, R., and Moriyon, I.

(1996) Outer membrane differences between pathogenic and environmental

Yersinia enterocolitica biogroups probed with hydrophobic

permeants and polycationic peptides, Infect. Immun., 64,

4891-4899.

32.Ho, N., Kondakova, A. N., Knirel, Y. A., and

Creuzenet, C. (2008) The biosynthesis and biological role of

6-deoxyheptose in the lipopolysaccharide O-antigen of Yersinia

pseudotuberculosis, Mol. Microbiol., 68, 424-447.

33.Felek, S., Muszynski, A., Carlson, R. W., Tsang,

T. M., Hinnebusch, B. J., and Krukonis, E. S. (2010) Phosphoglucomutase

of Yersinia pestis is required for autoaggregation and polymyxin

B resistance, Infect. Immun., 78, 1163-1175.

34.Aoyagi, K. L., Brooks, B. D., Bearden, S. W.

Aoyagi, K. L., Brooks, B. D., Bearden, S. W., Montenieri, J. A., Gage,

K. L., and Fisher, M. A. (2015) LPS modification promotes maintenance

of Yersinia pestis in fleas, Microbiology, 161,

628-638.

35.Guo, J., Nair, M. K., Galvan, E. M., Liu, S. L.,

and Schifferli, D. M. (2011) Tn5AraOut mutagenesis for the

identification of Yersinia pestis genes involved in resistance

towards cationic antimicrobial peptides, Microb. Pathog.,

51, 121-132.

36.Klein, K. A., Fukuto, H. S., Pelletier, M.,

Romanov, G., Grabenstein, J. P., Palmer, L. E., Ernst, R., and Bliska,

J. B. (2012) A transposon site hybridization screen identifies

galU and wecBC as important for survival of Yersinia

pestis in murine macrophages, J. Bacteriol., 194,

653-662.

37.Rebeil, R., Ernst, R. K., Jarrett, C. O.,

Adams, K. N., Miller, S. I., and Hinnebusch, B. J. (2006)

Characterization of late acyltransferase genes of Yersinia

pestis and their role in temperature-dependent lipid A variation,

J. Bacteriol., 188, 1381-1388.

38.Reines, M., Llobet, E., Llompart, C. M., Moranta,

D., Perez-Gutierrez, C., and Bengoechea, J. A. (2012) Molecular basis

of Yersinia enterocolitica temperature-dependent resistance to

antimicrobial peptides, J. Bacteriol., 194,

3173-3188.

39.Dentovskaya, S. V., Anisimov, A. P., Kondakova,

A. N., Lindner, B., Bystrova, O. V., Svetoch, T. E., Shaikhutdinova, R.

Z., Ivanov, S. A., Bakhteeva, I. V., Titareva, G. M., and Knirel, A. Y.

(2011) Functional characterization and biological significance of

Yersinia pestis lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis genes,

Biochemistry (Moscow), 76, 808-822.

40.Kiljunen, S., Datta, N., Dentovskaya, S. V.,

Anisimov, A. P., Knirel, Y. A., Bengoechea, J. A., Holst, O., and

Skurnik, M. (2011) Identification of the lipopolysaccharide core of

Yersinia pestis and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis as the

receptor for bacteriophage φA1122, J. Bacteriol.,

193, 4963-4972.

41.Hong, W., Juneau, R. A., Pang, B., and Swords, W.

E. (2009). Survival of bacterial biofilms within neutrophil

extracellular traps promotes nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae

persistence in the chinchilla model for otitis media, J. Innate

Immun., 1, 215-224.

42.Langereis, J. D., and Weiser, J. N. (2014)

Shielding of a lipooligosaccharide IgM epitope allows evasion of

neutrophil mediated killing of an invasive strain of nontypeable

Haemophilus influenza, MBio, 5, e01478-14.

43.Raetz, C. R. H., and Whitfield, C. (2002)

Lipopolysaccharide endotoxins, Annu. Rev. Biochem., 71,

635-700.{{anchor|PictureBullets}}