Identification of Proteins Whose Interaction with Na+,K+-ATPase Is Triggered by Ouabain

O. A. Akimova1, L. V. Kapilevich2, S. N. Orlov1,2,3, and O. D. Lopina1*

1Lomonosov Moscow State University, Faculty of Biology, 119991 Moscow, Russia; fax: +7 (495) 939-3955; E-mail: od_lopina@mail.ru2Tomsk State University, 634050 Tomsk, Russia; fax: +7 (3822) 529-852; E-mail: sergeiorlov@yandex.ru

3Siberian State Medical University, 634050 Tomsk, Russia; fax: +7 (3822) 420-954

* To whom correspondence should be addressed.

Received April 15, 2016; Revision received June 24, 2016

Prolonged exposure of different epithelial cells (canine renal epithelial cells (MDCK), vascular endothelial cells from porcine aorta (PAEC), human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC), cervical adenocarcinoma (HeLa), as well as epithelial cells from colon carcinoma (Caco-2)) with ouabain or with other cardiotonic steroids was shown earlier to result in the death of these cells. Intermediates in the cell death signal cascade remain unknown. In the present study, we used proteomics methods for identification of proteins whose interaction with Na+,K+-ATPase is triggered by ouabain. After exposure of Caco-2 human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells with 3 µM of ouabain for 3 h, the protein interacting in complex with Na+,K+-ATPase was coimmunoprecipitated using antibodies against the enzyme α1-subunit. Proteins of coimmunoprecipitates were separated by 2D electrophoresis in polyacrylamide gel. A number of proteins in the coimmunoprecipitates with molecular masses of 71-74, 46, 40-43, 38, and 33-35 kDa was revealed whose binding to Na+,K+-ATPase was activated by ouabain. Analyses conducted by mass spectroscopy allowed us to identify some of them, including seven signal proteins from superfamilies of glucocorticoid receptors, serine/threonine protein kinases, and protein phosphatases 2C, Src-, and Rho-GTPases. The possible participation of these proteins in activation of cell signaling terminated by cell death is discussed.

KEY WORDS: Na+,K+-ATPase, ouabain, coimmunoprecipitation, 2D-PAGE, mass spectrometryDOI: 10.1134/S0006297916090108

Abbreviations: AKT, protein kinase B; CAMTA1, calmodulin-binding transcription activator 1; CG-1, DNA-binding domain; CTS, cardiotonic steroids; Erk, extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase; IP3R, inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor; IQ, calmodulin-binding motif; Jnk, c-Jun kinase (stress-activated protein kinase); MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MEK, protein kinase MAPK/Erk; pHi, intracellular pH; PI3K, inositol-3-phosphate kinase; Raf, serine/threonine protein kinase; Rac and Rho, small GTP-binding proteins; RIPA, buffer for radioimmunoprecipitation; SGK2, serum/glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 2; TIG, transcription factor immunoglobulin/DNA-binding domain.

Na+,K+-ATPase (a sodium ion pump) is a transmembrane enzyme located in

the plasma membrane of all animal cells providing active transport of 3

Na+ and 2 K+ through the membrane against the electrochemical gradient.

The enzyme consists of two subunits tightly bound to each other. One

(the α-subunit) is catalytic, and the other (β-subunit) is

regulatory. Each subunit is represented by several isoforms

(α1-α4 and β1-β3), which are encoded by different

genes.

Ouabain and other cardiotonic steroids (CTS), originally found in plants and amphibia, inhibit Na+,K+-ATPase activity via specific binding with an extracellular part of the enzyme α-subunit. More recently, it was shown that several members of the cardiotonic steroid family (CTS) such as ouabain, digoxin, 19-norbufalin, marinobufagenin, and telobufotoxin are present in mammals [1]. Elevated levels of some CTS in the blood serum have been found in cardiovascular and renal diseases, including volume-expanded hypertension, chronic renal failure, congestive heart failure, and preeclampsia [2, 3].

In recent years, it has been shown in a number of laboratories that interaction of CTS with Na+,K+-ATPase, besides the inhibition of the enzyme, leads also to the activation of Src-kinase with following phosphorylation of epidermal growth factor receptor that results in activation of the Ras/Raf/MEK/Erk1/2 (p42/44 MAPK) signal pathway, production of reactive oxygen species, and activation of gene expression [1, 4-6]. Our laboratory first demonstrated that prolonged incubation with CTS (but not the inhibition of Na+,K+-ATPase in K-free medium) results in the death of canine renal epithelial cells (MDCK) and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) [7-9]. Epithelial cell death induced by CTS is characterized by combined markers of apoptosis (caspase-3 activation, nucleus condensation) and necrosis (cell swelling, membrane disruption). In contrast to “classic” apoptosis, this type of cell death is not sensitive to the pan-caspase inhibitor z-VAD.fmk. Further research has shown that elevation of the intracellular ratio of Na+ and K+ concentrations is a necessary but not sufficient step for induction of death in CTS-treated cells [10]. Using different methodological and pharmacological tools, we did not observed involvement of oscillation of intracellular Ca2+ concentration, activation of Ras, Erk, MAPK, phosphoinositide-3 kinase (PI3K), protein kinase C (PKC), endocytosis of Na+,K+-ATPase, and its translocation into the nuclei in the development of death signaling in ouabain-treated cells [11, 12]. More recently, we demonstrated a phosphorylation of p38 MAPK in CTS-treated cells of collecting duct of canine renal epithelium (C7-MDCK). Both p38 phosphorylation and death of ouabain-treated C7-MDCK cells were suppressed by p38 inhibitor SB 202190, but both processes were resistant to its inactive analog SB 202474 [13]. We also found that modest intracellular acidification (decrease pHi from 7.45 to 6.50) suppressed death signaling in ouabain-treated cells [14]. It should be noted that decrease in pH from 7.45 to 6.75 did not alter the level of p38 MAPK phosphorylation observed in ouabain-treated cells. Inhibitors of PKA, PKC, and PKG as well as inhibitors of protein phosphatases were unable to abolish p38 MAPK activation triggered by incubation of cells with ouabain [13]. However, the role of this signal cascade in the action of ouabain on the viability of other cell types was not yet investigated.

It is well documented that Na+,K+-ATPase interacts with dozens of proteins including anchoring proteins of cytoskeleton network (ankyrin, spectrin) [15, 16], Src-kinase [17], clathrin, adaptor protein 2 [18], caveolin-1 [19], inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor type 3 [20], and the regulatory subunit (p85α) of class IA phosphoinositide-3 kinase (PI3K) [21]. Taking this into account and understanding that CTS binding significantly changes the conformation of the Na+,K+-ATPase α1-subunit [22], we suggested that just the ouabain-induced change of α1-subunit triggers association (or dissociation) of Na+,K+-ATPase and unknown protein(s) that, in turn, leads to initiation of the signal cascade resulting in cell death.

Using the proteomics method, we try to identify in this study the proteins whose interaction with Na+,K+-ATPase is induced by ouabain and may be involved in activation of p38 MAPK.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture. Caco-2 cells, derived from a human colon carcinoma cell line, were obtained from ATCC (USA). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 µg/ml) and maintained in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2/balance air at 37°C. To establish quiescence, cells were incubated for 24 h in media with 0.2% fetal bovine serum. Then quiescent cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline and treated with 3 µM ouabain.

Estimation of cell viability. Activity of caspase and lactate dehydrogenase and the content of chromatin fragments were measured as described earlier [8, 10]. Cell morphology was evaluated by phase-contrast microscopy at magnification 100× without preliminary fixation.

Coimmunoprecipitation. Caco-2 cells were treated in the absence or presence of 3 µM ouabain for 3 h. Then the cells were transferred onto ice and washed with ice-cold phosphate buffered saline. Cell lysate were prepared by addition of RIPA buffer containing 0.5% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 3 µg/ml phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2.5 µg/ml leupeptin, 2.5 µg/ml aprotinin, 2.5 µg/ml pepstatin A, and 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4. Then the cell lysates were sonicated twice per 5 s and centrifuged at 100,000g for 1 h at 4°C. The supernatants were used for coimmunoprecipitation. To remove nonspecific binding, the same amount of protein from each supernatant was incubated with 200 µl pre-washed Pansorbin for 2 h on a rocker at 4°C. After low-speed centrifugation (1000g, 5 min), the resultant supernatants were incubated with shaking overnight at 4°C with mouse monoclonal antibody against the α1-subunit of Na+,K+-ATPase (clone α6F). To collect immuno-complexes, pre-washed protein-G-Agarose beads were added for 2 h at 4°C. Then the beads were pelleted, washed, and incubated with 5× Laemmli buffer or with sample buffer for two-dimensional gel electrophoresis.

Immunoblotting. Cell lysates and immunoprecipitates were separated using SDS-PAGE (4% stacking gel and 10% resolving gel). Before loading on the gel, the samples were denatured at 65°C for 10 min. Then the proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, blocked with 5% fat-free milk in phosphate buffered saline for 1 h at room temperature, and incubated with primary mouse monoclonal anti-Na+,K+-ATPase α1-subunit antibody (clone α6F) with shaking overnight at 4°C. Then horseradish peroxide-conjugated secondary antibodies were added, and the membrane was developed by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL).

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Proteins from each immunoprecipitate were denatured for 5 h on a rocker by addition of sample buffer containing 9 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 4% CHAPS, 1% Nonidet P-40, 40 mM Tris-HCl, 65 mM dithioerythritol, and 2% immobilized pH gradient buffer (pH 3-10). After centrifugation at 5000g for 5 min, the supernatants were loaded onto immobilized pH gradients strips (Ettan IPGphor, USA; 7 cm) and left for rehydration overnight at 20°C. Horizontal first-dimensional focusing was run to 15,000 V·h. The strips were equilibrated twice for 15 min in SDS-equilibration buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.8, 6 M urea, 30% glycerol, 2% SDS, 0.002% bromophenol blue) containing first 10 mg/ml DTT and then 25 mg/ml iodoacetamide. The second-dimension separation was performed on a vertical system as described above (see section “Immunoblotting”). Silver staining was carried out as described earlier [23]. The resultant gels were scanned and analyzed by ImageMaster 2D Elite Software (Amersham, Great Britain).

Mass spectrometry. Gel pieces containing selected proteins spots were treated with trypsin for 6 h at 37°C. Peptide fragments were extracted and analyzed by mass spectrometry (Agilent 1100 series; Agilent, Germany) [24]. Proteins were identified using Mascot (Metrix Science) with the NCBI protein database and Human Protein Reference Database (HPRD).

Reagents. The following reagents were used in this study: ouabain (ICN, USA); Pansorbin (Calbiochem, USA); mouse monoclonal anti-Na+,K+-ATPase α1-subunit antibody (clone α6F) and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were obtained from DHSB (USA) and Calbiochem (USA), respectively. Protein-G-Agarose was purchased from Sigma (USA). ECL reagents and strips with immobilized pH-gradient were from Amersham Biosciences (Canada). Trypsin was from Promega (USA). The remaining chemicals were from Sigma, Gibco BRL (USA), Anachemia (Canada), and Helicon (Russia).

RESULTS

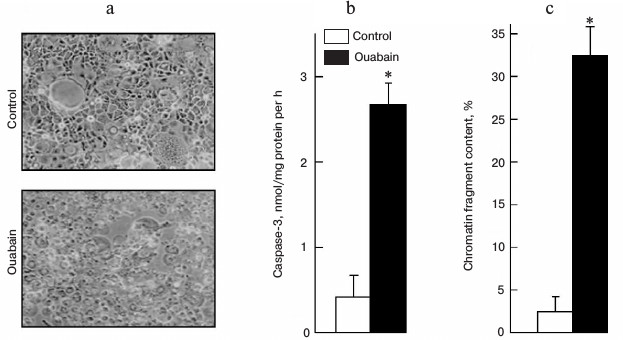

Figure 1a shows that treatment of Caco-2 cells with ouabain (3 µM) for 24 h leads to cell swelling and their detachment from the surface. This process is accompanied by caspase-3 activation (Fig. 1b) and by sharp increase in the content of chromatin fragments (Fig. 1c), which are canonic markers of apoptosis. The same type of cell death triggered by ouabain was demonstrated for canine renal epithelial cells [7] and for endothelial cells of porcine aorta [9]. We did not find a change in these parameters or in the activity of extracellular lactate dehydrogenase, a marker of necrosis, after the incubation of the cells with ouabain (3 µM), which is in contrast with a sharp increase in these parameters after the addition of staurosporine and hydrogen peroxide, which are canonic inducers of apoptosis and necrosis, respectively (Table 1).

Fig. 1. Effect of ouabain on morphology (а), activity of caspase-3 (b), and content of chromatin fragments (c) in human colon adenocarcinoma cells (line Caco-2). The cells were incubated for 24 h in the presence of 3 µM ouabain. Microphotography was made using phase-contrast microscopy at 100× magnification without preliminary fixation (a). Average values and values of mean-square error obtained from four experiments repeated four times are presented; * p < 0.01 (b, c).

Table 1. Accumulation of chromatin

fragments, activity of caspase-3, and extracellular lactate

dehydrogenase after 3 h incubation of human colon adenocarcinoma

cells (line Caco-2) in the presence of ouabain, staurosporine, or

hydrogen peroxide

Notes: Content of 3H-labeled DNA of chromatin and total

activity of lactate dehydrogenase were taken as 100%. Average values

and values of mean-square error obtained from four experiments made

four times are presented; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.001

relative to the control value.

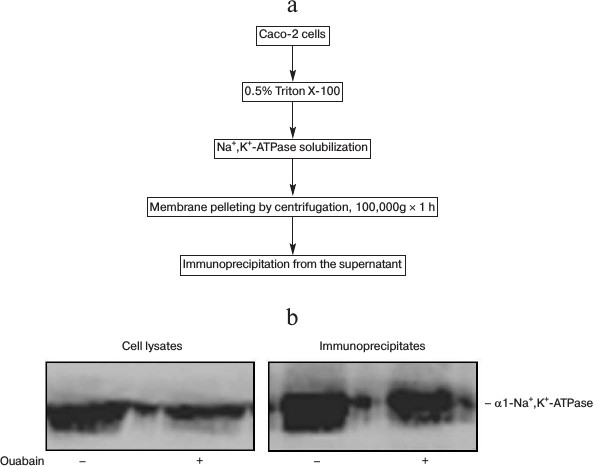

Taking into account these results, in further experiments the time of incubation was restricted to 3 h. After that cell lysates were prepared and immunoprecipitation was carried out with antibodies against Na+,K+-ATPase α1-subunit (Fig. 2a). Figure 2b shows that the presence of ouabain in culture medium and in the solutions used for immunoprecipitation does not affect the affinity of mouse monoclonal antibodies against Na+,K+-ATPase α1-subunit in lysates and in the immunoprecipitates.

Fig. 2. Scheme representing preparation of Caco-2 cell lysates (a) and results of representative immunoblotting (b) demonstrating the presence of Na+,K+-ATPase in cell lysates and immunoprecipitates obtained after treatment of cells for 3 h in the presence or absence of 3 µM ouabain.

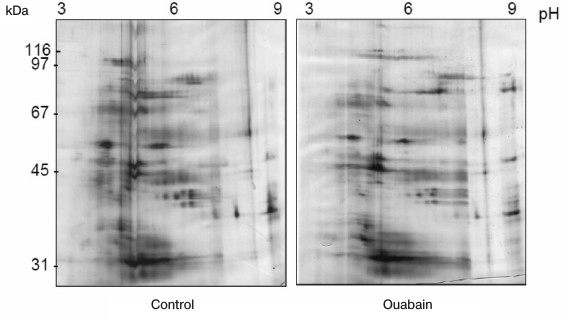

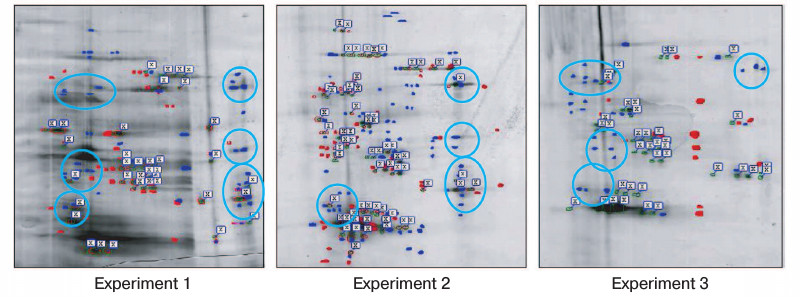

The immunoprecipitates were analyzed by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis. Based on the data of three independent experiments, we compared the profile of proteins that coimmunoprecipitate with Na+,K+-ATPase after incubations of Coca-2 cells in the presence or absence of ouabain using ImageMaster 2D Elite Software (Fig. 3). Comparing results of these independent experiments, we revealed more than 20 proteins with molecular masses 71-74, 46, 40-43, 38, and 33-35 kDa whose interaction with Na+,K+-ATPase is activated by ouabain (Fig. 4). Eighteen spots of proteins whose binding to Na+,K+-ATPase was triggered by ouabain were excised from gel and subjected to trypsinolysis. The products were analyzed by mass-spectrometry. The list of identified proteins whose interaction with Na+,K+-ATPase was activated by ouabain is shown in Table 2. Receptor of glucocorticoids, phosphoprotein phosphatase 2C, Src-kinase associated protein 1, Rac GTPase activating protein 1, calmodulin-binding transcriptional activator 1 (CAMTA1), casein kinase 1, and serum/glucocorticoid regulated kinase 2 (SGK2) were found among these proteins.

Fig. 3. Representative 2D-PAGE gels showing the protein profiles of control and ouabain-treated coimmunoprecipitates. Proteins are shown that are coimmunoprecipitated with Na+,K+-ATPase in the control and in the presence of ouabain.

Fig. 4. Comparison of gels demonstrating protein bound to complex Na+,K+-ATPase–ouabain and obtained after their resolution by two-dimensional electrophoresis from immunoprecipitates purified from lysates of Caco-2 cells after their incubation for 3 h in the presence or absence of 3 µM ouabain. The data of three independent experiments are presented. Red spots indicate proteins revealed only in the coimmunoprecipitate without ouabain treatment (control). Blue spots show the proteins that were found only in the coimmunoprecipitate after treatment with ouabain. The common proteins from both samples are marked with flags. Blue lines separate groups of ouabain-sensitive proteins having similar molecular masses and detected in two independent experiments. Proteins of these groups were later identified by mass-spectrometry.

Table 2. List of identified proteins

whose interactions with Na+,K+-ATPase were

stimulated by ouabain

Notes: Mr, relative mobility; MS, mass-spectrometry.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we examined the effect of ouabain on the interaction of proteins with Na+,K+-ATPase. The goal of the work was to reveal potential proteins that trigger signal cascade finally resulting in cell death. The hypothesis was based on data indicating that ouabain binding to Na+,K+-ATPase leads to a change in the conformation of the enzyme α1-subunit [22]. We suggested that this conformational transition may, in turn, induce the binding (or dissociation) of proteins in Na+,K+-ATPase–ouabain complex, thus triggering a signal cascade resulting in cell death.

Using coimmunoprecipitation with following two-dimension electrophoresis, we found a number of proteins whose binding to Na+,K+-ATPase is activated after cells treatment with ouabain. Their analysis by mass-spectroscopy let us identify some proteins, including seven signal proteins from superfamilies of glucocorticoid receptors, serine/threonine protein kinases, and phosphatases 2C, Src, and Rho GTPases (Table 2).

Earlier, it was demonstrated that Na+,K+-ATPase α1-subunit interacts with a number of proteins that can regulate activity and endocytosis of Na+,K+-ATPase as well as gene expression and cell proliferation. It is known that their interaction with Na+,K+-ATPase is realized via conserved domains of some of these adaptor proteins. Thus, ankyrin associates with Na+,K+-ATPase via interaction with two distinct domains of the α1-subunit and a repetitive motif consisting of 33 amino acids of ankyrin, the so-called ankyrin repeat [25, 26]. It was demonstrated that in COS-7 cells the interaction of ankyrin B to the N-terminus of Na,K-ATPase α-subunit and N-terminal part of inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R) plays a key role in the function of the Na+,K+-ATPase/IP3R signaling microdomain. The downregulation of ankyrin B attenuated the interaction between Na+,K+-ATPase and IP3R, reduced the effect of ouabain on calcium oscillation and NF-κB activation, but had no effect on the ion-transporting function and distribution of Na+,K+-ATPase in the membrane [27].

Using the NCBI and HPRD protein databases, we established that sequences of some of the proteins we identified include conserved domains that might be involved in the interaction with Na+,K+-ATPase (Fig. 5). Thus, calmodulin binding transcription activator 1 (CAMTA1) contains ankyrin repeats. That suggests that this protein could be a potential partner of Na+,K+-ATPase. Besides ankyrin repeats, CAMTA1 has two types of DNA-binding domains designated the CG-1 domain and the transcription factor immunoglobulin domain (TIG), and four IQ calmodulin-binding motifs. TIG domains are present in a large number of proteins, including transcription factors such as NF-κB [28] and Oli-1 [29], and cell surface receptors [30]. CAMTA1 has been shown to act as a transcription activator in a reporter expression system [31]. Further data on the functional role are scarce. Recently, we reported that the total numbers of differentially expressed transcripts in HeLa and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) treated for 3 h with 3 µM ouabain were 819 and 886, respectively [32]. We did not observe CAMTA1 among the identified ouabain-sensitive genes, but probably this protein is important for the regulation of gene expression triggered by ouabain.

Fig. 5. Conserved domains of proteins that were revealed in Na+,K+-ATPase–ouabain complex as a result of the analysis of the protein sequences using the NCBI and HPRD databases. Names of conserved domains: ZnF, zinc fingers in nuclear hormone receptors; HOLI, ligand binding domain of hormone receptors; PP2Cc, Ser/Thr phosphatases, family 2C, catalytic domain; EF, EF-hand, calcium binding motif; PH, pleckstrin homology domain; C1, protein kinase C conserved region 1 (C1) domains (cysteine-rich domains); RHOGAP, protein activating GTPases of Rac family; CG-1, DNA-binding domain; TIG, transcription factor immunoglobulin/DNA-binding domain; ANK, ankyrin repeats; IQ, calmodulin-binding motif; S/T kinase, catalytic domain of Ser/Thr protein kinase.

It was established that the interaction between the Src kinase domain and the third cytosolic domain of α-subunit of Na+,K+-ATPase is regulated by ouabain, the SH2-SH3 domains of Src being constitutively bound to the second cytosolic domain of α-subunit. Ouabain-induced changes in the conformation of Na+,K+-ATPase are sufficient to free the kinase domain of Src [33], which leads to Src activation and provokes downstream protein phosphorylation including endothelial grow factor receptor, caveolin-1 [17, 34]. Because of the permanent linkage between Src kinase and Na+,K+-ATPase, we did not detect this protein among those whose binding takes place in response to ouabain in our study. However, in the coimmunoprecipitates obtained after treatment of cells with ouabain, we found Src kinase associated phosphoprotein 1. This protein was identified recently as a novel substrate of a cytosolic protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP-PEST) that contains, in addition to its catalytic domain, several conserved domains that allow it to interface with several signaling pathways as well as to play a key role in the regulation of cellular motility and cytoskeleton dynamics [35].

Other proteins indicated in Fig. 5 contain also some conserved domains, including the catalytic domain of Ser/Thr phosphatases of family 2C, conserved region 1 domain of PKC, and the catalytic domain of Ser/Thr protein kinase. In our previously study, we reported that death of ouabain-treated C7-MDCK cells proceeded by altered phosphorylation of the RRXS*/T*-motif, which is located in four proteins with molecular masses from 25 to 80 kDa [36]. It was demonstrated that phosphorylation of the RRXS*/T*-motif is under the control of serine-threonine protein kinases including PKA, PKG, and PKC as well as serum/glucocorticoid-induced kinase (SGK), 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase (PDK1), and ribosomal S6 kinase (RS6K) [37, 38]. It should be noted in this connection that SGK2 is also among the proteins whose binding to Na+,K+-ATPase is activated by cell treatment with ouabain.

We found that glucocorticoid receptor, a member of the superfamily of nuclear receptors that are ligand-dependent factors of transcription regulation, also interacts with Na+,K+-ATPase. It was demonstrated that this receptor mediated in cells a number of events induced by stress, including the development of cell death [39]. Glucocorticoid receptor is usually located in the cytoplasm, where it binds to heat shock proteins HSP-70 and HSP-90, and from the cytoplasm it is transported into the nucleus. Regulation of transcription by glucocorticoid receptor is due to its interaction with DNA sequences that result in the activation or in the suppression of transcription. It is known that binding of glucocorticoids to the receptor may change transcription of up to 10-20% of the genes of the human genome. One can exclude that binding of glucocorticoid receptor to Na+,K+-ATPase–ouabain complex will decrease the amount of this receptor in the cytoplasm and in the nucleus, changing in this way the expression of some target genes. Up to now there was no information that glucocorticoid receptor can interact with Na+,K+-ATPase. However, it is known that it can interact with proteins of plasma membrane, in particularly, with caveolin 1 that, in turn, results in the development of antiproliferative effects of glucocorticoids mediated by activation of Src-kinase [40]. The number of publications demonstrating non-genomic mechanisms of action of glucocorticoid receptors is growing lately [41, 42]. Non-genomic effects due to the binding of glucocorticoids to their receptor may be realized via different mechanisms with the participation of some kinases such as PI3K, AKT, and MAPK. It was found, for example, that activation of membrane glucocorticoid receptors in HEK cells stimulates p38 MAPK [43]. We cannot exclude the possibility that interaction of glucocorticoid receptors with Na+,K+-ATPase in Caco-2 cells also can activate it, which might finally result in the activation of p38 MAPK and then in cell death.

Using the immunoprecipitation method, we revealed that ouabain induces the interaction of Na+,K+-ATPase with magnesium-dependent α-isoform of protein phosphatase 1A designated as protein phosphatase 2Cα (PP2Cα). PP2Cα is expressed in almost all animal tissues, where it is located in the cytoplasm and nucleus of cells [44]. Being an enzyme with broad substrate specificity, PP2Cα participates in the regulation of several important signaling pathways, including cellular stress, cell cycle progression, and cell growth [45]. Importantly, upon environmental stress, PP2Cα has been shown to inhibit the activation of both the JNK MAPK and the p38 MAPK pathways. Furthermore, PP2Cα and p38 MAPK could be coimmunoprecipitated, indicating that they also interact directly [46]. Our previous research demonstrated that ouabain and other CTS activated death signaling via phosphorylation of p38 MAPK [13]. Both p38 phosphorylation and death of ouabain-treated C7-MDCK cells were suppressed by p38 inhibitor SB 202190 but were resistant to its inactive analog SB 202474. Keeping this in mind, one can propose that ouabain induces inhibition of PP2Cα via its interaction to α1-subunit of Na+,K+-ATPase, which leads to phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and to the activation of death signaling. Additional investigation is needed to examine the role of the identified proteins in the interaction with Na+,K+-ATPase and development of death signaling triggered by ouabain.

Among the proteins interacting with Na+,K+-ATPase after its binding with ouabain, we found a Rac GTPase activating protein 1 (RACGAP1). There is now information concerning interaction of Na+,K+-ATPase with another protein activating Rab GTPase, AS160 [47]. This protein is involved in regulation of traffic and inserting of Na+,K+-ATPase in plasma membrane. Rac GTPase activating protein 1 participates in other cellular processes, in particular it is involved in cross-talk between Rho- and Rac-GTPases participating in the reorganization of cytoskeleton, cell transformation, and metastasis as well as in the formation of epithelial cell polarity [48]. Because death of Caco-2 cells is accompanied by their swelling and by the detachment from the surface (deprivation of cell polarity), one can suggest that binding of protein RACGAP1 to Na+,K+-ATPase plays an important role in the induction of cell death as a result of ouabain treatment.

Thus, using a proteomic approach, we identified a number of proteins that interact with Na+,K+-ATPase after cell treatment with ouabain and that may be involved in activation of p38 MAPK. Further research is needed to test this hypothesis and to understand the role of these proteins in the development of signal leading to cell death as result of the action of CTS.

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (projects Nos. 15-04-00101 and 15-04-08832) and by the Russian Science Foundation (projects Nos. 14-15-00006 and 16-15-10026).

REFERENCES

1.Schoner, W., and Scheiner-Bobis, G. (2008) Role of

endogenous cardiotonic steroids in sodium homeostasis, Nephrol.

Dial. Transpl., 23, 2723-2729.

2.Orlov, S. N., Akimova, O. A., and Hamet, P. (2005)

Cardiotonic steroids: novel mechanisms of

[Na+]i-mediated and -independent signaling

involved in the regulation of gene expression, proliferation and cell

death, Curr. Hypertens. Rev., 1, 243-257.

3.Bagrov, A. Y., Shapiro, J. I., and Fedorova, O. V.

(2009) Endogenous cardiotonic steroids: physiology, pharmacology, and

novel therapeutic targets, Pharmacol. Rev., 61, 9-38.

4.Tian, J., and Xie, Z. (2008) The Na-K-ATPase and

calcium-signaling microdomains, Physiology, 23,

205-211.

5.Aperia, A. (2007) New roles for an old Na,K-ATPase

emerges as an interesting drug target, J. Intern. Med.,

261, 44-52.

6.Orlov, S. N., and Hamet, P. (2015) Salt and gene

expression: evidence for

[Na+]i,[K+]i-mediated

signaling pathways, Pfluger’s Arch., 467,

489-498.

7.Pchejetski, D., Taurin, S., Der Sarkissian, S.,

Lopina, O. D., Pshezhetsky, A. V., Tremblay, J., De Blois, D., Hamet,

P., and Orlov, S. N. (2003) Inhibition of

Na+,K+-ATPase by ouabain triggers epithelial cell

death independently of inversion of the

[Na+]i/[K+]i ratio,

Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 301, 735-744.

8.Akimova, O. A., Bagrov, A. Y., Lopina, O. D.,

Kamernitsky, A. V., Tremblay, J., Hamet, P., and Orlov, S. N. (2005)

Cardiotonic steroids differentially affect intracellular Na+

and

[Na+]i/[K+]i-independent

signaling in C7-MDCK cells, J. Biol. Chem., 280,

832-839.

9.Boehning, D., Patterson, R. L., Sedaghat, L.,

Glebova, N. O., Kurosaki, T., and Snyder, S. H. (2003) Cytochrome

c binds to inositol(1,4,5)triphosphate receptors, amplifying

calcium-dependent apoptosis, Nature Cell Biol., 5,

1051-1061.

10.Akimova, O. A., Tverskoi, A. M., Smolyaninova, L.

V., Mongin, A. A., Lopina, O. D., La, J., Dulin, N. O., and Orlov, S.

N. (2015) Critical role of the

α1-Na+,K+-ATPase subunit in insensitivity

of rodent cells to cytotoxic action of ouabain, Apoptosis,

20, 1200-1210.

11.Akimova, O. A., Lopina, O. D., Hamet, P., and

Orlov, S. N. (2005) Search for intermediates of

Na+,K+-ATPase-mediated

[Na+]i/[K+]i-independent

death signaling triggered by cardiotonic steroids,

Pathophysiology, 12, 125-135.

12.Akimova, O. A., Hamet, P., and Orlov, S. N.

(2008)

[Na+]i/[K+]i-independent

death of ouabain-treated renal epithelial cells is not mediated by

Na+,K+-ATPase internalization and de novo

gene expression, Pfluger’s Arch., 455, 711-719.

13.Akimova, O. A., Lopina, O. D., Rubtsov, A. M.,

Gekle, M., Tremblay, J., Hamet, P., and Orlov, S. N. (2009) Death of

ouabain-treated renal epithelial cells: evidence for p38 MAPK-mediated

[Na+]i/[K+]i-independent

signaling, Apoptosis, 14, 1266-1273.

14.Akimova, O. A., Pchejetski, D., Hamet, P., and

Orlov, S. N. (2006) Modest intracellular acidification suppresses death

signaling in ouabain-treated cells, Pfluger’s Arch.,

451, 569-578.

15.Koob, R., Kraemer, D., Trippe, G., Aebi, U., and

Drenckhahn, D. (1990) Association of kidney and parotid

Na+,K+-ATPase with actin and analogs of spectrin

and ankyrin, Eur. J. Cell Biol., 53, 93-100.

16.Morrow, J. S., Cianci, C. D., Ardito, T., Mann,

A. S., and Kashgarin, M. (1989) Ankyrin links fodrin to the

α-subunit of Na,K-ATPase in Madin–Darby canine kidney cells

and in intact renal tubule cells, J. Cell Biol., 108,

455-465.

17.Haas, M., Wang, H., Tian, J., and Xie, Z. (2002)

Src-mediated inter-receptor cross-talk between the

Na+,K+-ATPase and epidermal growth factor

receptor relays the signal from ouabain to mitogen-activated protein

kinases, J. Biol. Chem., 277, 18694-18702.

18.Liu, J., Kesiry, R., Periyasamy, S. M., Malhotra,

D., Xie, Z., and Shapiro, J. I. (2004) Ouabain-induced endocytosis of

plasmalemmal Na/K-ATPase in LLC-PK1 cells by clathrin-dependent

mechanism, Kidney Int., 66, 227-241.

19.Wang, H., Haas, M., Liang, M., Cai, T., Tian, J.,

Li, S., and Xie, Z. (2004) Ouabain assembles signaling cascade through

the caveolar Na+,K+-ATPase, J. Biol.

Chem., 279, 17250-17259.

20.Miakawa-Naito, A., Uhlen, P., Lal, M., Aizman,

O., Mikoshiba, K., Brismar, H., Zelenin, S., and Aperia, A. (2003) Cell

signaling microdomain with Na,K-ATPase and inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate

receptor generates calcium oscillations, J. Biol. Chem.,

278, 50355-50361.

21.Chibalin, A. V., Zierath, J. R., Katz, A. I.,

Berggren, P. O., and Bertorello, A. M. (1998) Phosphatidylinositol

3-kinase-mediated endocytosis of renal

Na+,K+-ATPase α-subunit in response to

dopamine, Mol. Biol. Cell, 9, 1209-1220.

22.Klimanova, E. A., Petrushenko, I. Y., Mitkevich,

V. A., Anashkina, A. A., Orlov, S. N., Makarov, A. A., and Lopina, O.

D. (2015) Binding of ouabain and marinobufagenin leads to different

structural changes in Na,K-ATPase and depends on the enzyme

conformation, FEBS Lett., 589, 2668-2674.

23.Shevchenko, A., Wilm, M., Vorm, O., and Mann, M.

(1996) Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins silver-stained

polyacrylamide gels, Anal. Chem., 68, 850-858.

24.Wilm, M., Shevchenko, A., Houthaeve, T., Breit,

S., Schweigerer, L., Fotsis, T., and Mann, M. (1996) Femtomole

sequencing of proteins from polyacrylamide gels by nano-electrospray

mass spectrometry, Nature, 379, 466-469.

25.Zhang, Z., Devarajan, P., Dorfman, A. L., and

Morrow, J. S. (1998) Structure of the ankyrin-binding domain of

α-Na-K-ATPase, J. Biol. Chem., 273,

18681-18684.

26.Devarajan, P., Scaramuzzino, D. A., and Morrow,

J. S. (1994) Ankyrin binds to two distinct cytoplasmic domains of

Na,K-ATPase α-subunit, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA,

91, 2965-2969.

27.Liu, X., Spicarova, X., Rydholm, S., Li, J.,

Brismar, H., and Aperia, A. (2008) Ankyrin B modulates the function of

Na,K-ATPase/inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate receptor signaling microdomain,

J. Biol. Chem., 283, 11461-11468.

28.Muller, C. W., Rey, F. A., Sodeoka, M., Verdine,

G. L., and Harrison, S. C. (1995) Structure of the NF-κB p50

homodimer bound to DNA, Nature, 373, 311-317.

29.Hagman, J., Gutch, M. J., Lin, H., and

Grosschedl, R. (1995) FBF contains a novel zinc coordination motif and

multiple dimerization and transcriptional activation domains, EMBO

J., 14, 2907-2916.

30.Bork, P., Doerks, T., Springer, T. A., and Snel,

B. (1999) Domains in plexins: links to integrins and transcription

factors, Trends Biochem. Sci., 24, 261-263.

31.Bouche, N., Scharlat, A., Snedded, W., Bouchez,

D., and Fromm, H. (2002) A novel family of calmodulin-binding

transcription activators in multicellular organisms, J. Biol.

Chem., 277, 21851-21861.

32.Koltsova, S. V., Trushina, Y., Haloui, M.,

Akimova, O. A., Tremblay, J., Hamet, P., and Orlov, S. N. (2012)

Ubiquitous

[Na+]i/[K+]i-sensitive

transcriptome in mammalian cells: evidence for

[Ca2+]i-independent

excitation–transcription coupling, PLoS One, 7,

e38032.

33.Tian, J., Cai, T., Yuan, Z., Wang, H., Liu, L.,

Haas, M., Maksimova, E., Huang, X.-Y., and Xie, Z.-J. (2006) Binding of

Src to Na+,K+-ATPase forms a functional signaling

complex, Mol. Biol. Cell, 17, 317-326.

34.Yuan, Z., Cai, T., Tian, J., Ivanov, A. V.,

Giovannucci, D. R., and Xie, Z. (2005) Na/K-ATPase tethers

phospholipase C and IP3 receptor into a calcium-regulatory complex,

Mol. Biol. Cell, 16, 4034-4045.

35.Ayoub, E., Hall, A., Scott, A. M., Chagnon, M.

J., Miquel, G., Halle, M., Noda, M., Bikfalvi, A., and Tremblay, M. L.

(2013) Regulation of the Src kinase-associated phosphoprotein 55

homologue by the protein tyrosine phosphatase PTR-PEST in the control

cell motility, J. Biol. Chem., 288, 25739-25748.

36.Akimova, O. A., Lopina, O. D., Tremblay, J.,

Hamet, P., and Orlov, S. N. (2008) Altered phosphorylation of RRXS*/T*

motif in ouabain-treated renal epithelial cells is not mediated by

inversion of the

[Na+]i/[K+]i ratio,

Cell. Physiol. Biochem., 21, 315-324.

37.Peterson, R. T., and Schreiber, S. L. (1999)

Kinase phosphorylation: keeping it all in the family, Curr.

Biol., 9, R521-R524.

38.Lang, F., and Cohen, P. (2001) Regulation and

physiological roles of serum- and glucocorticoid-induced protein

kinases isoforms, Sci. STKE, 18, RE17.

39.Vyas, S., Rodrigues, A. J., Silva, J. M.,

Tronche, F., Almeida, O. F., Sousa, N., and Sotiropoulos, I. (2016)

Chronic stress and glucocorticoids: from neuronal plasticity to

neurodegeneration, Neural Plast., 2016, 6391686.

40.Matthews, L., Berry, A., Ohanian, V., Ohanian,

J., Garside, H., and Ray, D. (2008) Caveolin mediates rapid

glucocorticoid effects and couples glucocorticoid action to the

antiproliferative program, Mol. Endocrinol., 22,

1320-1330.

41.Groeneweg, F. L., Karst, H., De Kloet, E. R., and

Joels, M. (2012) Mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptors at the

neuronal membrane, regulators of nongenomic corticosteroid signaling,

Mol. Cell. Endocrinol., 350, 299-309.

42.Samarasinghe, R. A., Witchell, S. F., and

DeFranco, D. B. (2012) Cooperativity and complementarity: synergies in

non-classic glucocorticoid signaling, Cell Cycle, 11,

2819-2827.

43.Strehl, C., Gaber, T., Lowenberg, M., Hommes, D.

W., Verhaar, A. P., Schellmann, S., Hahne, M., Fangradt, M., Wagegg,

M., Hoff, P., Scheffold, A., Spies, C. M., Burmester, G. R., and

Buttgereit, F. (2011) Origin and functional activity of the

membrane-bound glucocorticoid receptor, Arthritis Rheum.,

63, 3779-3788.

44.Lifschitz-Mercer, B., Sheinin, Y., Ben-Meir, D.,

Bramante-Schreiber, L., Leider-Trejo, L., Karby, S., Smorodinsky, N.

I., and Lavi, S. (2001) Protein phosphatase 2Cα expression in

normal human tissues: an immunohistochemical study, Histochem. Cell

Biol., 116, 31-39.

45.Lammers, T., and Lavi, S. (2007) Role of type 2C

protein phosphatases in growth regulation and in cellular stress

signaling, Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol., 42,

437-461.

46.Takekawa, M., Maeda, T., and Saito, H. (1998)

Protein phosphatase 2Cα inhibits the human stress-responsive p38

and JNK MAPK pathways, EMBO J., 17, 4744-4752.

47.Alves, D. S., Farr, G. A., Seo-Mayer, P., and

Caplan, M. J. (2010) AS160 associates with the

Na+,K+-ATPase and mediates the adenosine

monophosphate-stimulated protein kinase-dependent regulation of sodium

pump surface expression, Mol. Biol. Cell, 21,

4400-4408.

48.Citi, S., Guerrera, D., Spadaro, D., and Shah, J.

(2014) Epithelial junctions and Rho family GTPases: the zonular

signalosome, Small GTPases, 5, 1-15.